lyle pittenger

contents—click on a chapter

1—Early life and enlistment

My name is Everett, E-v-e-r-e-double t, Lyle Pittenger. Of course I’m a junior and I was a junior in the service. I dropped that in later life. I was born on May 8th, 1918. Route 3, Wellston, Ohio. I had three sisters and two brothers. I’m the second child. I have an older sister and the rest younger.

I grew up on a farm. A hundred–acre farm, general farming. That’s in Milton Township. Back in those days it was horse–drawn equipment, and we had milk cows and just general farming. We had some pigs and hogs and calves, chickens, that type of thing. Chores started rather early in those days, at seven to eight years old, going and getting the cows, actually starting to help milk and different chores. Feeding the chickens, gathering eggs, things like that. We progressed, we went on to heavier, bigger work, of course. I was young when they started hoeing corn and working in the gardens in those days.

I’ve enjoyed gardening and it’s a challenge any more. It seems like they have more different types of insects and of course we have better materials to combat the insects and different methods to grow things.

My first four grades of elementary school were at Locust Grove Country School. That was near my home. Mulga, in Milton Township. About three–quarters of a mile from our home place. We walked to school. Back then the township roads were terrible, a lot of them, and that was one of the worst ones. I completed the fourth grade there.

It was one room, all grades together in one room, with the old pot–bellied stove in the center of the school and the blackboard on one end. There were eight grades. Sometimes a grade would only have three or four. I’d say on the average of twenty to twenty–five students altogether.

One teacher. Had the recitation up in front of her desk in the front end of the school on the blackboard end. The seats graduated from little up to bigger and as you went from one year to the next of the class, why you got in bigger seats. The eighth graders, you know, seventh and eighth graders, they’d be in the bigger seats. The teacher was the only adult.

My mother was a old one–room country school teacher. She taught in that school two years. That was before my time. My first teacher was Odessa Hammond. Her husband was in the post office for years and years, and they of course raised a family after they were married. What was his name? Emerson Mossbarger.

The Milton Township school board closed Locust Grove, Mulga, and the one out at, we called it Number 3 or Wainwright. They closed three schools, and that left them the Berlin Township Schools. They bussed the Mulga and the Wainwright or Number 3 children into Wellston. The Mulga one–room school was the first old one–room school in that neighborhood.

From the home place to the post office in Wellston was just right at three miles, and we went into the Fourteenth Street, they called it the South or the Fourteenth Street School. I’d say that that was right at two and a half miles. I think they had three busses. Levi Jolly, Homer Jones and I think there was one that went into Berlin from out in the old Buckeye Furnace neighborhood. Levi Jolly and Homer Jones went from Mulga and out that direction into Wellston. I don’t know whether it was Wesley Geer or somebody else that took the outlying ones that lived out over Carmel Hill and out toward Number 10. You’ve probably heard of Number 10. This was 1927 or 28. I think they closed it, they closed it in the fall of ’27, so it went in the ’28 school year, 1928 school year. I went to Wellston through the eighth, and on up to Wellston High School. I’m proud to say that I graduated in 1937.

Now for some reason, and to this day I never could get it established, but I was supposed to go to the fifth grade. When we got to Wellston and entered the school, they set us fourth graders back, and we had to take the fourth grade over again. They said it was on account of the books.

Differential in the books. So we lost a year there, you might say. I should have graduated in ’36. Sometimes people have narrowed me down, you know. “What’d you do? Flunk a year?” No, we went to the fourth grade again, and then went on up through the eighth and through high school. We lost a year as a result of being in the small rural school with the wrong books.

C.H. Jones was principal. Mr. Holter was the high school superintendent at that time. In high school my favorite subjects were industrial arts and history. I made average or a little above average grades.

I had a lot of good teachers. I might as well say my favorite teacher was Philip Dye, who was the general science teacher and commercial arithmetic. I knew I was weak in arithmetic when I started in high school, so Mr. Dye had general science, physics, chemistry, but he had an open class and he taught commercial arithmetic. So I took one year of that. It was a one–year thing, and he really helped me. There was a whole class of us took it, and I think I benefited greatly by that.

I did not have very many outside activities. Farm kids in those days were expected to help. They had chores and of course the time that we had to walk from home to school and back in the evening, so my sports activity was very, very limited. In high school we had physical education, and of course that was just like an open class. I mean they carried it once a week. We took that.

I know I was a good–sized boy, and my cousin Ever and Herb Tucker, you know Herb Tucker. And Alfred Bishop and us boys were healthy boys and we’d hear little remarks “I wonder how’s come he’s not on the football team?” Or, “ How’s come he didn’t come out on football or play basketball or something?” We couldn’t. We didn’t have time. We was expected to be home. Our fathers worked, you know, and we had chores to do. If we’d a practiced till, Wellston School, till say five o’clock, it’d been dark when we got home.

I’d like to tell you this. One Fall, oh, it was a terrible hot Fall, dry, and they dismissed school at three o’clock. Everybody was tickled to death and said, “Boy oh boy, aren’t you glad they’re dismissing school?” I said, “Well, not really.” Because I know what I’m gonna do when I go home. Dad was still putting up hay. I’d put up hay till dark! I’d just soon stay in school.

I used to think hay season would never end, and the farmers, it was a different ballgame then. They tried to get every bit of it. You cut the wheat like in July and of course you had a pretty good year of rain, well there’d be pretty good hay on that by September. They’d mow that and then put that up as hay too, you know, for roughage. They depended on it. Needed it. The cattle you know. They don’t do that much anymore. They have this equipment that makes it much easier.

During the Depression we were not hurt as bad as some others because we had a farm. We were well supplied with basic essentials, but we had no money. If you got a hold of a nickel, you really had something. The folks give us a little money now and then, but in comparison today we had no money in those days. What you got was what Mom got on Saturdays when she went on her...in those days country people went to town on Saturday and you’d go shopping and come back and that would be it. Kids didn’t run to the store.

Every evening or on the way from school. We just didn’t have it. We had chickens, several chickens and meat in the Fall and young chickens would lay, and they would depend on the chickens’ eggs, and some butter money and things like that. My mother sold eggs and butter in the town.

Dad mostly fed his grain and hay out, but sometimes he’d have a surplus, like in the Spring of the year. The phrase “fed it out” means fed it to the cows. Your own horses and cows. There’d be maybe a surplus left over in the Spring, why he occasionally sold a hundred bushel of corn or some hay, and it usually went into buying fertilizer or planting the corn or oats.

Back in those days farmers usually had cribs and they’d harvest their corn and crib it, meaning store it on the cob. Sometimes they’d take small amounts in and have it shelled and ground up and mixed a supplement for the cows and made chicken feed, but most of it was held over on the cob.

Through the 1920’s and up to 1935, the furnaces had gone down. Milton Furnace, the Upper Furnace. Those furnaces had gone down. The big mines had worked out. The Superior Coal Company and the Fluhart Coal Company, they had deep shaft mines through the later 1800’s and up through, up until about 1920, along in there, and it seemed like it was just about all worked out at the same time.

The mineral played out, and they moved their mines someplace else. When they did that, it seemed like the miners...there was a big percent of the people that depended on mining in the Wellston area. We called ’em the old time miners, you know, and it seemed like very few of ’em ever moved on with the companies. They just stayed there and beat it out some way.

Of course through the ’20’s it was terrible, and then in the early ’30’s they got the WPA going and things like that they worked out. The hard times began in the 1920’s through here.

So many places we talk about up to Wellston is out over Number 2 Hill or out at Number 3. Well those were mines. Number 2 was a shaft mine at the foot of Number 2 Hill, and they called that Number 2 Hill. Out the other way past Morrows and out toward Raccoon Creek, that was Number 3. On Number 8 Pike toward Uncle Frank’s, well there was a mine out there. It was Number 8 Mine, and it’s kind of funny.

They just, within the last two years, filled in Number 2. That was just an open shaft, three or four hundred feet deep. Boy, I was glad when they filled that thing up. I think they’ve pretty well got ’em filled up now. Dangerous. There was Number 9, Number 10, Number 12, Number 11. That’s on toward the far end of the county. Out toward, you’re goin’ toward Wilkesville, out in that area. Superior Coal Company had a lot of mines.

Then those furnaces had mines of their own right in Wellston that went down, oh, two, three hundred feet to down at that good Number 2 coal. You had a very high grade Number 2 coal from Wellston down through Coalton and toward Glenroy and down in there. They even went to the extent that those mines joined together. I’d say today there’s millions of gallons of water down there in those mines. Excavated mines, you know.

Yeah, they’re all filled up with water. That holds ’em up, too, you know. It’s in there and some places do give in sometimes, but not very often anymore. Wellston has had two or three settlements right up there in the middle of town.

Down in Jackson, to my knowledge there was Globe and Jisco furnaces. Old Star was right above. I started to work for the B & O Railroad on March 11th of 1941, and right back of where Chun King is now was huge concrete remnants of Old Star Furnace. It had already gone. And Orange and all those. Jisco and Globe was the last ones.

That pretty well covers it. Our recreation in the summertime was, like Saturday afternoon or Sunday after we’d go to church, us boys in the neighborhood would go down on Raccoon Creek and go swimming. Do you know where Little Raccoon goes down through Milton Township? It’s about three miles from home. Oh, later on we got bicycles. And we hunted after we got old enough to, that we could take dogs and guns. We hunted small game.

The game would kind of come and go. Sometimes the rabbits was very scarce. It was even said that they got something that kind of wiped ’em out for several years. They made a comeback. There were enough to have a good time if you had pretty good dogs.

The squirrel population, the squirrels held on better than the rabbits. Of course they lived in the woods in the trees and had a different food, depended on more nuts and things like that. I think the rabbit had more common enemies than the squirrel, too. Vultures came in. We’d berry pick up in that country, and they live on rabbits. I think back then there was a lot more woods.

Back in the mid–1800’s and through the Civil War time, these charcoal furnaces, around those areas, I’ve got an old atlas and I’ve read a lot about it. They just practically stripped the hills and the woods for charcoal. That’s what, a hundred and fifty years ago. The woods have come back.

Out of school, jobs were very hard to get. I applied at the pants factory. It was built I believe through the school year of 1936. How I know, my brother–in–law went to work on the first group of pressers in the initial plant, which was just a little plant. They made fine men’s trousers, Hercules Trouser Company. Later bought by the Kuppenheimer Company, and they kept expanding. I stayed around on the farm and, for ’38 and then I went in the coal mine and I worked through what we call three seasons in the coal mine, under the hill, number 4 coal.

It seemed like the mining season, Bill, started, it would start up late August and it’d run through say early April, and then they’d just sort of dwindle out. It was cold weather. It was mostly house coal. Practically everybody heated and cooked even with coal. So the market was better in the winter.

It was just sort of a private. Up in those hills, they was just dotted with small mines, and they was private mines. Most of ’em was a limit of four or five men. It was what they called slope mine usually, slope a little bit to get into the vein and then most of us had small cars that would hold, oh, 1800 to a ton, and we’d pull ’em out with ponies. Used ponies to pull power.

We’d go several hundred yards into the hill, some of ’em. We went all the way through some of the hills and have air shafts down on the far side of the hill for ventilation. Of course, as we went, most of it was slate top, and we had mine timbers cut all the time. As we went ahead we’d timber, set the columns, props or posts along as we went. The rooms would be something like twenty feet, and then if driving double rooms they’d leave like a six or eight foot column, they call ’em pillars. We speak of pillars, that was solid coal and that supported it. They wouldn’t stretch it too far, you know, to the top. We didn’t remove that coal because we needed it to support the roof.

And every eight to twelve feet, why they’d break through just enough that a person could...for an escape hatch. If something happened over here, if it didn’t get him, he could go through there and get into that other room, like if there’d be a weak place or a slate fall. And then it let ventilation, it caused the circulation of air, too. These tunnels were interconnected for safety reasons usually. You felt more comfortable if you knew you could get through if something happened over here where you were you could get through on the other side and get out.

I was never involved in an accident. Very lucky. Once you worked in there, why you get accustomed to it. You know signs that you pay attention to. If it’s bad enough you abandon or you get out of there till, maybe for a period of time to see what it’s gonna do. Now sometimes like the roof on the edge of that ceiling, if you had an overburden and sometimes you had worked, you didn’t know it, but maybe you worked under a huge boulder of lime or something, and you had wet weather, maybe along the edges you could hear it chipping. You’d hear it chipping along. Well, you know there was a lot of pressure there, and it’s time to get out and leave it alone for awhile. Sometimes on more extreme cases, we’d gone in and maybe a few of the posts would be almost a collapse. You could tell they were under stress. Yeah, time to get out of there. Quit that.

Miners usually went to work pretty early. Six–thirty to three, three–thirty. That was about. Miners usually went to work pretty early, and then they’d knock off about three. We were paid by the ton of coal. We got a dollar and a quarter a ton of coal. Not overburden. That coal went over the screens and sometimes you would lose some on what they call a screening. Dirt, you know. You just can’t get it all clean as it ought to be, but it worked out pretty good. Two of us we could run five ton a day, so I don’t know what that adds up to. Divide it by two.

Big wages. Then the miner, in those days we bought our own powder and supplies. We used carbide lights, and we had to buy carbide. And had to buy blasting powder and fuse and paper to make the cartridges out of. That come out of our diggin’.

We were a small operation, and there was no union. There was a union in the bigger mines, and once in a while when they’d come out on strike, why they’d come around and tell us. We’d just take a little vacation till they’d leave, you know what I mean. We didn’t aggravate ’em ’cause they was all our friends. Down in what they call Mohawk they had bigger mines down in there. Then stripping come in later years, early strip mining, down in, they call that Mohawk or down at, from Number 10 down in that part of the county.

When the people up in the Hocking Valley would...you know that was quite a mining place, Nelsonville, Canaanville, all up in there was a lot of mining up there. Well, they was really hard–nosed union men, and when they’d be trains of them come down maybe they’d come around and so we never give ’em any trouble. We just come out for a while until things got settled down. We never scabbed on them. Nobody ever asked us to, and we wouldn’t have scabbed.

We just took a little vacation. Everybody was happy. I had relation up in the valley. I didn’t want to get on them. I didn’t want to get Uncle Jim and all his boys on me. It was a good bit easier to cooperate. Well, that went on until the spring of 1941. The fella I worked with there at the last, his father worked with us till he got the age that he quit and he sort of retired. John Drummond and I went ahead with it, and John’s younger brother Ernest was working on the maintenance of way for the B & O Railroad.

He knew how the mine tapered off in the spring, so he mentioned to me one day. John told me one day, “Ern said they’re gonna hire, they’re gonna put a few men on for the summer on the B & O.” He said “Would you be interested?” And I said “Yes, I would.” So I got with him, and he filled out my applications and they sent me to Chillicothe and I was examined by the railroad examiner and passed the physical exam with flying colors. Eyes, many things. Eyes, hearing, colors. Colors was a real thing then on a railroad. They wanted you to know from a red flag to a green flag, you know. So, sure enough, March 11th ’41 I went on the railroad.

My first job was trackman. I started here at Jackson. A trackman, those gangs at that time was about four trackmen and a foreman, and we all worked together. If we was putting in ties we all worked on that. If we was laying some rail we all worked, we just worked together. Maintenance of way. That’s what we were, maintenance of way.

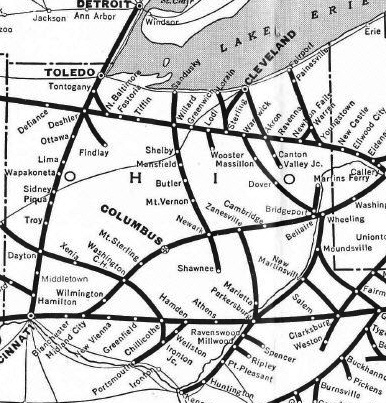

I was on the Portsmouth Branch of the B & O. It starts off at Hamden, comes down through, now they had a section from Hamden down through Wellston and down to Berlin. This section here went from Berlin, from Jackson up to Berlin and down to Keystone. We had, let’s see, eleven miles of main track and then they counted it three mile over to Jisco. We were responsible to maintain that track, plus the Jackson yards. It’d just be a rough guess, side tracks and all, the Jackson yards might as well add at least another mile and a half or two mile, anyway.

Classification yards where they did their switching and storing, the empties and the loads. The trains would come in with loads, you know, and they had to have a place to set them. Then as they did their work, they’d get more loads and take empties in their places, and that’s what the yards are for.

At that time we had one passenger train. It come out of Portsmouth every morning and went to Parkersburg. It was a diesel electric unit with two coaches, and that same train come back, over and back every day. For local traffic, it was just occasional, maybe somebody was just coming up to Jackson for the day or over to Athens. A lot of ’em went over to Athens to shop and then catch it coming back.

The B & O track ended down at the steel mill, at the lower end of Portsmouth. They left the Portsmouth Branch at Hamden. That’s a main line. If they wanted to go parts east and west, they’d go from Portsmouth up to Hamden and then switch to another train. At that time there was Eleven and Twelve and National Limited. Parkersburg was east on the main line from Hamden. Chillicothe was west. Just across the river and you come to the Parkersburg yard and their depot is just real close, right over to the other side of the river bridge. One passenger train every day. They just had the unit and they carried the mail and the baggage car and then one coach.

There was also what they called a Chillicothe local. It come out of there...back in those days was steam you know, a big steam engine...it come out of there headed toward Portsmouth. It come out of Chillicothe every morning, and it would make its way to Portsmouth. Chillicothe to Hamden to Portsmouth. Come down the west wye and into Wellston and I don’t think they did much at Wellston, but they usually had the furnaces running then. They usually had several cars to set off here at Jackson, and he’d work his way on by, and of course Oak Hill was humming with the brick industry at that time. It had boxcars, maybe a whole string of boxcars to set off down at Oak Hill.

Now this local, he went to Portsmouth, then he’d head back to Chillicothe. Usually he’d come back in here, oh maybe around midnight or two o’clock in the morning or if it was light work maybe ten o’clock, but anyway he went back to Chillicothe. At that time they had the long hop and facilities up at Wellston for these locals. There was a local left Wellston for Portsmouth every morning, and one left Portsmouth for Wellston every morning. They’d pass someplace from Oak Hill, according to the work. They’d work all these sidetracks. They both had empty cars, and they’d start out and they’d put in empties for of course what their agents had lined up to do.

All the manufacturing plants would have had track off the railroad track into the plant. Sidetracks. Now this Chillicothe local, his big load would be steel from down in Portsmouth. Steel was a big thing down there, you know, and that was its main business. It went to Detroit and all over the United States, Bill. Wherever they needed steel.

They did not carry a great deal of coal. There was some coal in places like down at Clay and down below Oak Hill. There was a few coal docks. They called them coal docks, where’d they load hoppers of coal. But it was mostly brick and steel from the steel mill and brick from the Oak Hill area and on down for clay products down in the southwest part. I can’t remember all the little old switches that went into clay mines, just the bulk clay. That’s why we had a brick industry here. We had good clay, and plenty of it.

In addition to the B & O there was the C & O Railroad. C & O come out of Logan. The C & O come out of Logan down through Wellston on down through Coalton that way, and the B & O come down through Berlin and down through Petrea at that time. Each railroad company had its own track network. That’s the C & O over there by the old cigar factory or over by the foundry, and he dead ended right behind Globe Furnace. That was the end of their line. Globe had a yard on that side where they’re kinda figuring on makin’ a park and that was the C & O yard. Below Water Street. They had several tracks in there. So did B & O and D T & I.

The D T & I ran over...by agreement, they ran over the B & O from right over there at what we call the light plant, you know, over on Broadway. They went onto the B & O right there and come over past and got orders at the depot, and then they ran. They couldn’t pick up or set off anything until they went off of the B & O down at Bloom Junction. That’s this side of South Webster. Before you make that big curve going up to Webster. Well, they went off to the left and toward Ironton. So D T & I actually ran over B & O track in a good part of Jackson County, and we maintained the track. D T & I couldn’t do any work between there. If they did, they had to share or give it to the trainman and the B & O. If they break down they could set off. If a car’d break down or something, why they could set off in our sidetrack and notify the agent, but they couldn’t do any switching or pick–up or set–off cars.

D T & I run a lot of coal from down Ed Clark’s Pedro and down in that country. They picked up a lot of coal and brought it up. They took a lot of it on to Ironton, too. You know as they get onto the N & W. They’d turn it over to the N & W and she’d go on a big track up north. They had a good railroad down through there, and it worked out real nice. Now that, that was six days a week. For years and years they run to Ironton and back.

At that time we had three railroads in Jackson County, each with its own set of customers. Each had its own track except D T & I ran on B & O track by agreement.

Bill, maintenance of way was just what it says. We maintained the track and we tried to keep it in good shape. In the summertime you can put ties in when it’s not frozen, you know, and things like that. Well, they’d have a tie program from like the last of March through August, they’d put in ties mostly. Mow, keep the right–of–way clean and do crossing work.

We had on the average a foreman and four men and sometimes they’d upgrade that in the summertime to maybe eight men to increase production, get more done. They didn’t like to have too many men around when it was frozen up. About all you could do would be tighten bolts. We did all that by hand, too, in them days. Big wrenches, you know, and go along and tighten bolts and replace ’em if they was bad.

On the joints that held the rails together. The rails, most on the main lines the rails were thirty-nine foot long. Some of ’em was thirty-three foot and some rail was thirty foot six. Most of it down the branch here was a hundred pound rail, upgraded from the old eighty-five. Now we’ve got a hundred and we’ve got some hundred and twelve pound rail down here. All the yards and every sidetrack had switchlights that burned kerosene that had to be refilled, cleaned and lit or checked twice a week. You’ve seen those switchlights. Now they do that with, most of it’s done by machinery.

The old handcarts on the rails? Well, Tom Hughes and Loren Mercer, they had twenty years service when I joined ’em over here on March 11th, and they had taken the old handcars in just a few years before and they come out with motor–driven cars. The Fairmount Company built motor cars, and they was a one–cylinder belt–driven outfit.

We drove them up and down the tracks. You’ve seen these little push trucks. Four–wheel push trucks at the coupling. We need to take out ties or cadge the bolts or you know, just transport heavy stuff. Rail. We could haul rail, switch points. Those old motor cars, boy, settin’ out there like a bunch of birds on that limb, we’d about freeze to death.

I went home one evening, you know. Us guys a certain age...I think it was October the 16th. 1940. I got my card in my billfold, that we all a certain age of us had to register for the U.S. Army. They registered you, all the men a certain age.

Let’s see, about July 20th the next year I come home and I had a letter from the President of the United States telling me to report to the draft board, 9 o’clock on the morning of August the 12th, 1941. I got a greetings, and I was gonna be with him or the Army for one year. That year stretched out to three years nine months and five days.

This was before Pearl Harbor. So, on that appointed day, why I went to the Courthouse and Clark Cleland was head of the draft board they call it, from Wellston. Clark Cleland. He was associated with the Milton Banking Company and a very nice gentleman. He was head of the draft board at that time, so he met us there and had our orders in a big envelope. There was three of us. Wilma’s brother and Hal Edwards came from Oak Hill. We walked up to the Gibson House and waited for the bus that left about 9:15 there.

We just got our orders and got on that bus. We come down through Oak Hill and on to Portsmouth, picked up two or three guys along the way that had notified them that they’d be standin’ out along...people did that then, they’d catch a bus down toward Firebrick, down in there, you know. Rather than to come to Oak Hill or someplace, why they’d just flag the bus down and get on and go on.

We got down at Portsmouth and oh, the group would be about eight or ten by that time, I guess. A whole flock of guys got on at Portsmouth, and we started for Huntington. We got on another bus that went from Portsmouth to Huntington. Then by the time we got that Huntington Armory, why, there was a whole busload of us. A lot of the guys had come from West Virginia cross into, they got orders to meet ’em at Portsmouth. You know, across the river. Different places. A lot of West Virginia and some Kentucky boys.

We went to the old Huntington Armory. They met us over there, of course, with the vehicles at the bus station. They took us direct down to Huntington Armory. As I remember, I was drafted directly into the United States Army with no choice at all. We just had our orders to report and, as far as I know, we all went into the Army. We was the only three out of the county of that call, and I’ll say about two to three weeks before that a buddy of mine and several guys was in the first call. That’d be, oh, middle of June.

We were the second call. The last time before that would have been First World War.

Well, then, they took us to hotels and gave us our lunch and loaded us up and took us down to Huntington Armory. We was examined, full physical examined there at the Huntington Armory. When they got done with this particular group, why we were all sworn into the Army. I was 23 years old at the time. I guess I had a feeling of apprehension and fear and bewilderment. I mean, you know, on that day you completely change from one life to another. I mean at that hour. And I didn’t have a great deal to say about it.

I think most people that was really concerned about war coming. I know I heard the older folks talkin’...could well remember World War I. I think they could see that we was gonna get in another war.

We were inducted about 4 o’clock in the evening, and we got a grand pay of $21 a month for four months, and then if we didn’t goof off or something, why at the end of four months we got $30 a month. Boy, we really got a raise.We had to pay our insurance and laundry. And we all had to buy cleaning equipment for the rifles. We had to buy a bottle of Hoppe’s and two or three things to clean ’em or an extra shaving brush to clean our rifles with. We had to buy a lot of shoe polish because we scuffed up our shoes pretty bad in basic training, so we had to keep our shoes shined.

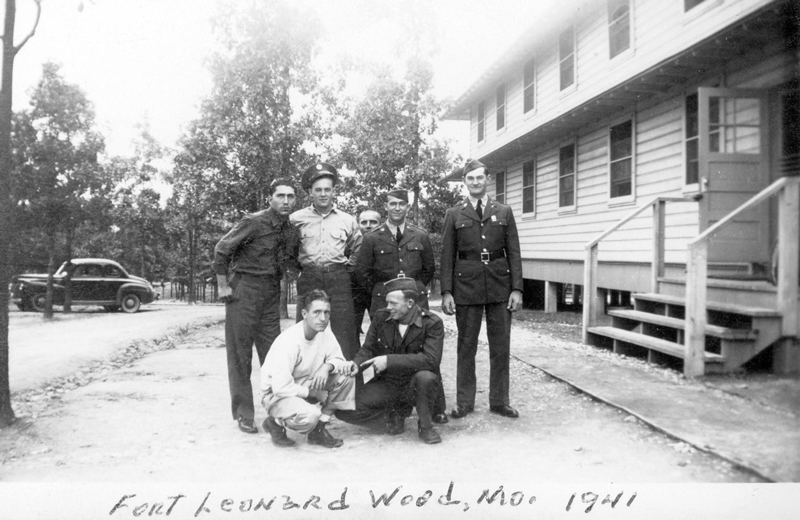

We shipped out from Huntington the next day, afternoon, and went down to Fort Thomas, Kentucky, and they unloaded us down there. We went by train. We went by train from Huntington. Boy, that was really a treat, get to ride on a passenger train. They assigned us to barracks down there at Fort Thomas, and the next day they started givin’ us our shots. First series of shots. We were there about three days, I think, and they sent (of course it’s hard to keep track, you know there’s guys comin’ and a goin’, you know) but the group I was with, they sent us to Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri.

We were Ohio and West Virginia boys and a sprinkling of Kentucky. Mostly Ohio, but a good many, say about a third maybe, were from West Virginia and then a scattering of Kentucky boys. They gave us some testing. I believe they did take us in a couple places, groups of us and they had us to fill out some forms. Of course an instructor went along with each thing and it was kind of a mark “yes” or “no” or a choice of something like that. It wasn’t much really to concentrate on it because you didn’t know really what it was all about anyway. I think that was the main object, to try to figure out the ones that could read and write and ones that had been, say from elementary school to high school and if there was any in college. I think that’s what it was about.

2—Basic Training

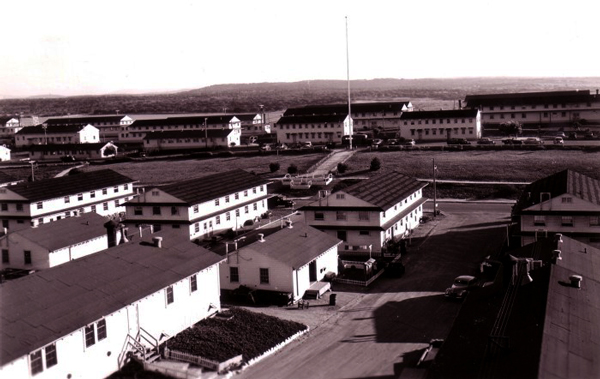

Fort Leonard Wood was a brand–new fort or post. It was a fort named after General Leonard Wood of World War I. He was a famous general there. The government bought, I think, a good part of Missouri down on Big Piney River for way back, about ninety miles from St. Louis. Boy, it was back in the woods.

I think we were the second group that was in there, and they was building barracks furiously and churches and rec halls and kitchens and building the hospital. Putting up water towers. They was actually constructing then. They used us, a lot of our manpower, to help do a lot of those things, just as training. Fort Wood was basically an engineer training center.

Naturally they had the headquarters way out and then the huge drill field. Then they had, off in every direction, they had different parts of training areas, you know. A lot of ’em were really out in the woods, too. I expect it was five mile maybe from the post down on the Big Piney River—they had their pontoon and bridging school down there. I kinda had a feeling that they run records, what we did in civilian life, and I thought maybe since I worked on a railroad, that maybe I got in the engineering department.

In Basic Training, you get up in the morning and you stand reville. You been through that. You stand reville, you get your breakfast right quick and you got so many minutes to go to the bathroom and shave. You had to look up on the bulletin board on the side of the orderly room what the first uniform was. Whether it was fatigues or o.d.’s or khaki. We went in khakis first.

So, whatever it was, why that’s what you put on, and then when the whistle blew you fell out in the ranks. Maybe they’d close order drill you or march us over to a big drill field and you go through maybe a half hour or so of drilling. By platoons and companies and battalions and all that. Then maybe they’d take you back and you had fifteen minutes to change from your khakis into fatigue clothes and fall out under arms with leggin’s.

It tickled me, I was tellin’ Wilma, they said “Fall out with leggin’s, under arms.” Some of the guys fell out with their leggin’s under their arms, and they said, “Get back in there and get them leggin’s on!” Poor guys, they done what they told them to. “Fall out with leggin’s under arms.”

Well, then, Bill, in engineering we started to basic engineer. A lot of it was done way back in the woods with hammers and just regular wood tools. We’d cut down trees and cut ’em up and build bridges across ravines and just whatever the Army needed. We’d build tank traps and things to...like we’d set posts, and put another log up on there, and then just over a little further set a nail. A tank try to come through in the night they’d run up on them and get hung up on them. Stuck, you know.

Usually second lieutenants and staff sergeants did the training. They’d been through it enough they had it down pretty pat. We also had night problems, map reading, compass work. There was emphasis on engineering from the very beginning. This was Engineering Basic Training. Different from regular infantry basic training. Besides, we got infantry training over on the drill field, and we’d have days that we just did infantry training. Rifles, you know. And different formations and different signals, without saying anything, you know.

By squads, platoons, and we had lots of bayonet. At times we had lots of bayonet drill. The Army still drummed on the old bayonet, and we’d drill and drill on the bayonets. How to stab it down in. Like a company, they’d string us out in two big long rows. You with a bayonet and me with a club, but we’d keep the scabbard on. Take it off your belt, so we wouldn’t really hurt each other. You didn’t aim to hit anybody, but you’d see that man goin’ through the formation, and you’d visualize what he was gonna do to you. Maybe you’ve been through bayonet. Did you have any bayonet drill?

Really down in the bayonet there’s steps that you went through with, if you missed the first plunge you didn’t just back up and take off again. You had another option. The short, the short and the long and the butt cut...slash, you know, and it was really somethin’. It seemed awful horrible. I’m thankful I didn’t end up doing that.

Pontoon is of course using the assault boats. The small hand–operated assault boats, where each squad had to do their own rowing and go across the river and get out of the thing and, and make a charge up over the hill and get that done, get back in and get across without upsettin’ or somebody gettin’ drowned. Then that was part of it and then we went into foot bridges, putting foot bridges across, and then, playin’ like we was the infantry, goin’ across the foot bridges on attack. Then graduated up to the bigger ones where a jeep could cross, actually up to where a two and a half big truck could cross.

They really put it to us. They had the material stacked, like a school you know, they had the material. Now down on pontoon, up in these other training areas where we cut all the timber ourselves in assigned patches. They had it patched out you know. They didn’t at random cut the woods down. They just cut a few, enough to demonstrate, you know. Sometimes use the other stuff that they had.

We built what they call the bent type bridges, like we use today you know, the bents and then the stringers and the decking. We worked, a lot of us, with ropes. We had lots of classes with ropes, tying of knots and different hitches, and threading block and tackle. They’d team us up on block and tackle and see which gang could set a block that could drag the other ones. Things like that made it more interesting.

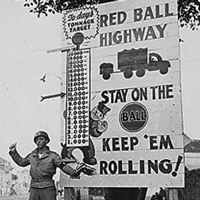

We had very little training at Basic on heavy equipment, but we had a little bit of training with a little R-4. The R-4 was a gasoline cleat tractor. He was a little small cat. But some of the boys that was more adapted to that, well they give them more training than others. They didn’t drum that too much. If a fella, if his records...they kept pretty close records of us of course. If you seemed to be adapted in the mechanical end of it or something or equipment operator, you might end up in H & S Company, heavy equipment and supply.

The Army really tried to screen us at an early time so that they wouldn’t waste a lot of time with somebody that wasn’t adapted at all for engineering work or try to train somebody for heavy equipment into something else that they could use ’em otherwise. Move things along better. We took several tests along that line and it leveled out pretty good.

The sergeants, as far as I’m concerned, were well qualified. I don’t just know how many groups they had worked with, but not very many. They seemed to be well qualified to pass on their knowledge and training to us. We were one of the first groups that these sergeants were training. It was really a new fort, and construction ever’place and right beside our unit there was new buildings going up. Each battalion had their PX, their church, and rec hall and of course their barracks and kitchen altogether.

Discipline and drill was quite strict. They didn’t allow any clowning around. It wasn’t just all drudgery, but they kept us busy and kept us training pretty well.

The weapons in the Basic Engineers. We trained with World War I Springfield ’03 thirty caliber rifles with bayonet, and we practiced grenade throwing with dead grenades. No live grenades. We got the idea of the proper way to throw a grenade, and we had some hand–to–hand combat training. I got the impression that we would probably need this training, combat training right along with the engineer work. I thought that they were trying to get us accustomed to the different procedures and what we might face on that.

Personally, I didn’t have any injuries in Basic Training. We had a few fellas that got working with tools. Some of the fellas had never seen a two–man crosscut saw or adze or had a real good sharp axe. We had a few injuries, but nothing real serious, I’m happy to say.

The barracks were the double story with the latrine and showers on the ground floor, and they were large enough to have two squads down and two squads up. Twelve to thirteen men to a squad. So this would be a platoon barracks. They had a coal–fired furnace outside the entrance in the front of the building on the ground floor. It was back near the showers, on that end and the toilet facilities. It heated the water for the showers.

Upstairs was a little room that would accommodate about four non–coms, but our platoon non–coms stayed right in the barracks with us. For the Company area we laid out the three barracks, kitchen on the upper end and the supply. The supply and order room shared the same building right on the end.

We started out with a canvas cot, folding cot, just for a few days, and they brought in a single one–person bunk. Single, with mattress. It was a metal cot.

The barracks were standard design, all over the Army.

I can’t remember of any women at Fort Leonard Wood. No. Even over at headquarters I can’t remember there was any women. Our medics seemed to be all men, giving shots and doctors, all men personnel. Nor can I remember any black soldiers at the Fort.

We had very few passes. We were pretty much on base. They seemed like that they had a pretty tight schedule and they wanted to get it worked in, so not very much. Along toward maybe about the tenth week of the thirteen weeks they started a lettin’ a few go into St. Louis, which was ninety miles away. They had buses that ran from the Fort into there, and all the outlying little villages which wasn’t very close were off–limits. Had to have a pass if you stepped over the line.

They had a rumor around that the group before us had one suicide. A fellow got depressed and they didn’t get to it soon enough. After they got into going to the rifle range he’d evidently smuggled a round of ammunition and shot himself in the barracks. In one of the little upper rooms. That’s about the only tragedy I can think of. Now that was before, that was a group before we got there.

Thirteen weeks Basic Training and it was getting up toward Thanksgiving time and we finished up and I remember the fellas began to ask about “Are we gonna get a leave? Are we gonna get a pass?” Well, they didn’t tell us exactly. Finally it narrowed down. “The next place you go you’ll get a ten-day leave and you can go home for ten days and then report back.” But that didn’t work out for me very well. I don’t know how about the other fellows. I was the only one out of my company that was picked for the group that was set aside to go to Ford Ord, California.

So, the appointed day that we loaded at, and the government had built a brand–new railroad out to Fort Leonard Wood. They had a yards out there that they brought in freight, supplies, and they’d bring out the coaches you know, that they’d transport troops on. So that’s where we loaded, right there. And we moved out. A troop train to Fort Ord.

Loaded us up on the train, and we headed for Fort Ord, California. “What about my furlough?” “They’ll give it to you once you get to your new place.” So you know, strange thing, now you know you didn’t, in thirteen weeks, I was in Company B of the Twenty–second Battalion at Fort Wood. In the company there was four platoons, and you know I was the only guy out of our company that went to Fort Ord. You know where Fort Ord is. It’s at Monterey, California. It’s right on the ocean, and it was an old World War I regiment and that was its home base. They was in France during World War I, and all regulars, you know. Here’s us first selectees. They called us selectees and draftees for a while, but that’s where I joined the outfit.

We went the northern route. St. Louis seemed to be a great big railroad hub, you know, Southern Pacific and Missouri Pacific and railroads that I’d never heard of. The B & O was what I was used to, sort of ended at St. Louis. And we went the northern route. I think we went on the Great Northern or one of those routes, and went down through the Grand Canyon. They stopped the train down just to let us look a little bit, up and down the Canyon.

It was something to see, a railroad goin’ down in there, and then I know we could, as we went up out of there, we could look up ahead at the three steam engines pulling the train up that way, and one pushing on the back. It was like a snake and we could look across and see ’em, hard to realize that you was on the same train. The last night, without seeing daylight, you could tell that you was quit climbing and you was going, it seemed like something told you you was going down, which we were. We’d went over the Divide, I guess, and was going toward the Coast and we stopped at Denver, Colorado about eight o’clock in the morning and what is it, Pike’s Peak over there. That was something for us to see, you know. There was snow way down on it. It was gettin’ up in November, and they begin, well there was a two or three inches of snow on the ground there then. That was the first snow we saw. Then we went on over to Fort Ord.

3—Fort Ord and the Pacific Coast

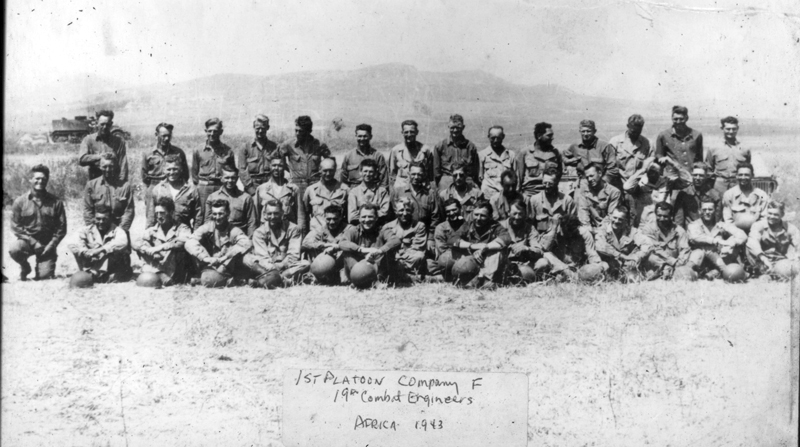

Ford Ord is right on the coastline. Just look out the various windows and right down there’s the beach, beach of the Pacific. It’s at Monterey, California. North of Los Angeles and south of San Francisco. We joined the 19th Combat Engineers Regiment. It was a regiment—six line companies and H & S Company. H & S Company is Headquarters and Supply. The line companies were designated A through F.

We were the first group of inductees or selectees that they had got. I thought I might bring that in because, see, we wasn’t volunteers. We were selected to the 1941 build–up in the Army. I’d say 95% of us. Some guys jumped in and volunteered just as soon as that happened, but most of us just went with the current and went in. We went in for one year training and service, and we understood that if we didn’t get into a war, they just wanted to train us and just have us sort of in reserve. But the situation changed right quick. We were basically soldiers in the Army, for good.

We were regular Army. We weren’t in the reserves. In answer to your question when did we get there, on the third day after we arrived the Japs hit Pearl Harbor. Now how I remember so well, all but just a skeleton force was left at...they knew we was coming of course, and they just left some non-coms and some officers and people to transport us. The rest of the whole outfit was out in the desert. What is that, the Mojave Desert? They were back there on maneuvers, so it took ’em a few days to get us there and get us our equipment. We didn’t have anything. We had to be issued our web equipment and our rifles and all that equipment.

I think about the third day they loaded us up and took us out there. It was quite a long ways, several hours’ run out there. So I believe the next day...I was remembering that as soon as I got there, I was put on what they call a machine gun guard. Of course Army always had guards out, you know. Well, I was on a .30 caliber machine gun.

We joined the maneuvers, and they had this post on a real high point of a hill, right overlooking the camp, and we were there that night. The next morning about nine o’clock the Sergeant sent me down on an errand to...I can’t remember just what it was, whether it was for some rations or water or something, and he was just a regular sergeant. The Staff Sergeant, as soon as he saw me, he said go back and tell Sergeant Reeves to fold up his post and bring ’em down, that we’re moving back to Ord. That the Japs had hit Pearl Harbor. So, we wasn’t there very long after us new fellows got with them. We loaded up. By evening we’d broken camp and was on the way back to Fort Ord.

Do you want me to start with an individual company? There were three platoons, with three squads per platoon. Now they might run up as many as fourteen men to a squad. I’d say the basic privates and a sergeant and a corporal. Full strength, I believe that runs to about fourteen men to a squad, see, and then three squads to the platoon. Then there was a staff sergeant over the buck sergeant and then there was a first or second lieutenant that was the platoon commander. And the staff and once they got their T.O. of officers, why our first officer was first lieutenant of the company, but they were short of non–coms and officers.

Sergeant Green was an old Army regular. He was the First Sergeant of the company when I joined, and Captain Stogsdale, he was an elderly individual. He wasn’t with us but just a short time, but he was the captain. He was the company commander, Captain Stogsdale.

In basic platoons, they were riflemen at that time, and the mechanical operators were in the H & S Company, Headquarters and Supply. They had like a platoon in Headquarters and Supply, and part of that platoon was the equipment operators and truck drivers and those fellows.

The line companies would be basically doing engineer work, but they was quick to lay down the tools and fall into fighting, combat mission, which quite often happened. The privates would be construction laborers, and the sergeants, like in civilian labor, the sergeant would be the foreman or the boss. Whatever we was doing, bridging, building roads, clearing, clearing areas for something new or just whatever the situation was.

Each man had his rifle and bayonet, and when the situation changed, they issued each squad a water–cooled World War I type thirty–caliber machine gun. We also had live grenades, but they was kept under lock and key until we actually needed ’em. Later on, while we were still in California, each platoon was issued a 37 milimeter anti–tank gun. Along with that, each platoon was issued a half–track. The half–track was different from the infantry.

A half–track. It’s unlike a tank. It’s not enclosed on the top, or it doesn’t carry a mounted gun like a tank. It’s open–topped, and it was manufactured by the White Truck Manufacturing Company. It had a motor that had White on it. W–h–i–t–e. They was tremendously heavy, and the front part was just standard truck, guided front wheels, and then the back part was track. It would run on a highway or off. It was all rubber. The tracks were unlike the older tanks that were all metal tracks. They had rubber pads on the tracks. They were fast, too.

It was a new piece of equipment. The older fellows of the 19th said that they hadn’t had that. It apparently was a newly developed vehicle that the Army had adopted. It carried what we later called a weapons squad, and it was mounted with a fifty caliber machine gun, belt type.

As I remember, they’d take the platoon and the three squads, and they collected the best men that the rifle range records showed, with guns. They picked three men out of each squad and built up a weapons squad. They were assigned a half–track. When we fell in formation, that really made four squads. See what I mean? Instead of three squads, we made four squads.

When we were just in bivouac or normal times, we fall out in company formation. Instead of having a truck, they had the half–track. Normally there was a squad of men in each truck. On the other squads I was talking of, about a fourteen–man counting the NCO’s squad, each had their own truck. Standard Army truck. Each squad in each platoon had its own truck for transportation. Each platoon had three trucks and a half–track. Plus they also had a jeep. They got beucoup brand–new jeeps. Willys jeeps. They didn’t have this stuff before.

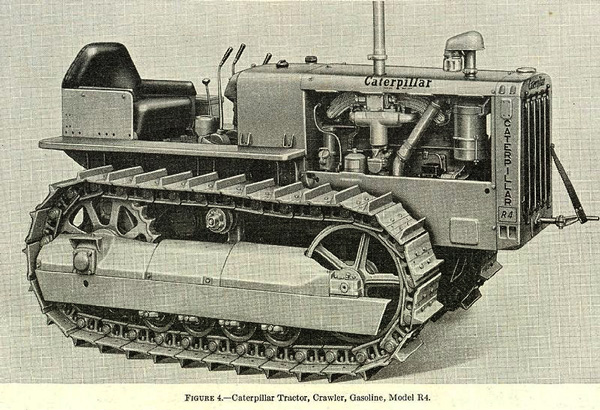

We were ready. We didn’t have to walk. No, we didn’t have to walk a lot, they just wanted us to. We did a lot of walking, on hikes, and a lot of times ten miles. Well, we walked it. Each company at that time had a R–4 gasoline tractor bulldozer. You know what I mean? They was a cleat tractor, bulldozer. They called ’em an R–4. That’s a small one. Then later on, when we got into business, each company got a D–7, and then they upgraded to D–8. That was diesel–powered bulldozers which would make about three of the R–4.

We had heavy bulldozers overseas. Now this H & S Company, that was their responsibility. They had what we called prime movers. Huge, but they, at first they called ’em four ton trucks. Then, before it was over with, we had six–ton tandem, huge trucks that pull these low–boys that haul these huge D–7 and 8 bulldozers. That’s when we got really ready for business.

I don’t know how many they had, but we had like the county has these patrol graders. We had those with us to grade, make roads, air landing strips, anything that they needed. They were fast, they would run fast on the road. They were mounted on rubber. You know, just like you see now. They haven’t changed ’em a whole lot. We called ’em patrol graders.

This was at the company level. They were very useful. Most of the roads once we got overseas were like our secondary roads and the Army beat ’em to pieces. They were a great help to us to keep ’em leveled and maintained. When we got into North Africa, within four or five hours we could take one and make a landing for fighter planes.

In North Africa through Tunisia there was valleys of level ground and it seemed like we’d get away from the foothills and where the boulders were. We could take those patrol graders and make a landing strip in just a short order for the fighter planes or even the big boys. But they, the bombers, usually come from distance. Fighters kept pretty close to us.

Later on we got bazookas. You know what we mean about the bazooka? It was a rocket, battery fired. The bazooka. Each squad had a grenade launcher. One man was designated and given additional training on rifle grenade. They’d shoot a grenade three or four hundred yards, pretty accurate after a fellow got used to holding the rifle. That was the main thing. Usually they’d sit ’em on the ground in a leaning position and hold ’em at an angle. It took practice and training, a lot farther than you could throw one.

Then we got in this mine warfare. We carried land mines with us, a certain number in each truck. Headquarters kept that stuff as close as they could, but we couldn’t carry everything. We did take like fifty mines on three trucks. That’d be a hundred fifty of ’em. We could mine an area if they called for us to land mine. Anti–tank mines mostly.

In addition, now from the time we hit Fort Ord we had a gas mask all the time with us. That gas mask, there was a bill that went around the shoulder strap and it hung right under your left arm, and we had to take that thing to chow, but maybe I’d better back up a little bit. Once the Japs hit Pearl Harbor we went into a new chapter in warfare. If we left our tent to go just to the latrine or the kitchen or the orderly room, we had our steel helmet on. At that time it was a World War I doughboy hat.

Helmet, a rifle and a gas mask. And a cartridge belt, you know. That was something, too. It didn’t make any difference if you was just goin’ like from here to the garage you had to have that with you, and it was just gettin’ that tight.

The gas mask would smother you to death it seemed like, especially if it was real hot. You’d get that face mask on and it had to be air–tight under your chin, and the mask, it had a netting over your head and very uncomfortable. We never did use them in action. At the end of North Africa they took ’em all to the supply room and put ’em in big boxes. Those gas masks followed me completely across North Africa, but it was a precautionary, a safety thing.

We didn’t know what the Japs were gonna do, especially in California, and maybe I should back up. Do you remember when a Japanese submarine raised up close enough to shell the coastline below Los Angeles?

A lot of people don’t believe that, but at 9 o’clock this night, the orders come in for us to, with arms, load up as fast as we could. We were camped about two miles out of Pasadena, California, up a draw, at Devil’s Gate Dam. That was a water–saving dam that they have out there to catch the water in the wintertime and hold it for water supply.

What we did, when we moved from Fort Ord, you see they evacuated a great part of Fort Ord when the Japs hit Pearl Harbor. They practically evacuated Fort Ord. We, 19th Engineers, went down toward Los Angeles, spread out down in there. We, F Company, happened to go in there at Pasadena, and we cleaned up abandoned CCC camps. You know how things will grow up, and the three C’s had kind of phased out. The buildings were kind of shabby looking. They had headquarter buildings and two or three buildings there like they built, and they were just low long–like buidings, but we used them for the headquarters, and we quartered in pyramidal tents. Pyramidal tents will take care of, let’s see, about ten men.

In the pyramidal tent, the center pole went up and fastened to sort of a harness up there, but when it got up it wasn’t square like that, you know. It had about six corners. It looked like it had about six corners. It was handed down from World War One.

Other than that we had pup tents. Each soldier had a shelter half and one pole and six tent pegs. Two soldiers could go together and put up a pup tent. You are familiar with the old pup tent. They were great! If it was raining and you turned over, your shoulder rubbed the side and it started dripping right down. Did you know that? It would start leaking. “Don’t touch that tent!” Turn over and accidentally... Us tall guys, our feet was just barely in, you know.

Each company had their allotted place in pyramidal tents. This night at nine o’clock, a call come in. They rushed us down and we put up a defense up along the coast there. The Jap submarine had fired several rounds before we got there, and a few after we got there. A lot of people said that’s not true, but we saw they had a chain–link fence around the Sun Oil Company. You have probably heard of the Sun Oil Company. In California. They had these storage tanks up there, and a high chain–link fence around the whole thing. Most of the shells hit the fence and exploded. We saw holes shot through the fence. A couple tanks they hit just slightly below the top of the tank. Put a hole in them like that. About six or eight inches across.

I don’t know what size projectile it was. With the gauge of the tank, you know, it would hit it and bend in. I don’t exactly what size it was. But, luckily, it didn’t set them afire. We were certainly glad, because it would have been an awful explosion, a tankful of fuel. We stayed there all night up until noon the next day, and then they called us back to Pasadena. The sub left. We didn’t see it, though. The unit got a Congressional citation and the American Defense Ribbon for that little bit of action.

So within a few days we were spread out towards San Diego and Santa Barbara area there, with our equipment, digging in 155 artillery pieces for coastal defense. Now maybe I shouldn’t say this, but as far as coastal defense, we couldn’t see another thing along our west coast in the way of armament for defense. Maybe they had it on back someplace, but they rushed us down there and we took bulldozers and made gun emplacements for them and we dug powder magazines. With the dozers, and timbered them up. The coast was not previously defended.

Back to organization, there was three line companies in the battalion. And a headquarters company. And two battalions in the regiment. First and Second Battalions. Companies would be A, B, C, D, E, and F. Six companies in the Regiment. Our commanding officer was a full colonel. When we went there the First Battalion that they had us at, the commanding officer was Colonel Porter. He was an elderly looking soldier. He was a Lieutenant Colonel. Right away the commander...now he was the Commander of the whole Regiment...right away Colonel Moore. Evidently the Army was shifting their officials around and we got Colonel Moore, and he was a full colonel. He was the man with the eagles on.

We used that Devil’s Gate Water Reservoir for training pontoon and bridging. It made a nice place to play with our pontoon equipment there. A floating bridge.

They had us practicing doing everything. We took soundings, like shoot a mark over there and send a couple guys over there in a rowboat and they put up a stake. Then we’d follow that line and measure every so many feet to see how deep it was, and make a graph out of it. It come in handy once we got the natural bridging or crossing rivers. It come in handy. We knew what they was talking about, at least.

All the pontoon equipment was like plywood construction. The pontoons were wood construction. Open top with beams fastened right on them for your timbers to lay on. You know, your treadway. Once we got over in the combat area, especially up in Italy...we didn’t have to do much of that kind of work in North Africa or Sicily. But we got started up through Italy, we got into rivers, you know, and there was almost one hundred percent air–inflated pontoons. They could deflate them, and one truck could haul so many of them when they was rolled up.

One other piece of equipment. Each company had an air compressor. A mounted air compressor. It was a LeRoi...manufactured by the LeRoi Company. They were just invaluable. Built on this six–by truck. Same chassis as the six–by truck. The motor and the compressor was right in one unit, and it had tool boxes on each side. It had the drills, the jackhammers, hose, and everything. They was just really a valuable piece of equipment. Do more work with them things. Even on ground for digging a latrine. We’d get the jackhammers for garbage pits. They was really a valuable piece of equipment. Now that was something new in the Army, too.

The last of June, getting up into July, we upgraded our equipment. Polished it. Getting ready to move to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey. So it took us a while. We had to load all those vehicles onto cars, and tie them down. You know what we mean by come-alongs. Rolls of wire. Everything had to be just right. Blocked and chocked, you know. Lot of work to it. Moving those vehicles. Getting ready the equipment...went right with us.

We went the Southern route. From Pasadena we went the southern route back East. We crossed Oklahoma and Texas. Then they went right straight towards St. Louis and from there up to Chicago. We stood in the Chicago yards the biggest part of one afternoon.

We had the equipment on train cars, and then there were coaches, Pullman coaches. We traveled by Pullman. I think we were just about all on one train. Maybe it was two trains. I’m not sure. We got to Camp Kilmer...it took us six to seven days to travel that far. At that time with the train traffic that was on the roads. It took us about a week to go, there all the way across to Camp Kilmer. We were there right about the first of August, 1942.

4—Shipping out overseas

There were lots of engineer regiments in the army. I know there was Nineteenth Engineers, Twentieth Engineers. There was Forty–Eighth Engineers. About every division had their combat engineers in World War Two. Probably one engineer regiment per division. A division had about fifteen thousand men.

At Camp Kilmer we didn’t unpack. I don’t know where they parked our equipment, but we didn’t even have our own trucks. They had their own trucks there at Kilmer if they wanted to take us on a motor hike or something like that. They wanted to get guys used to riding in trucks, you know, and loading and unloading. At times tempers, you know...you’d get all loaded up and you’d go about half a mile down the road and they’d stop all at once. “Everybody out. Get out and line up on the road.” They were just getting us used to in and out. In a group doing things in a hurry. Pretty good idea, I think.

More training. I don’t know where they had our equipment parked. Our heavy equipment. We didn’t have any. We were there through the month of August. The first day of September, 1942 we loaded on the British ship Queen Elizabeth, sister ship to the Queen Mary. The first day of September at nine o’clock that morning she eased out and headed straight down by the Statue of Liberty, got out in the open water, and took right straight across. When we loaded and went down and got on the train, every man had his full field pack, rifle, that infernal gas mask, the whole works. We had been issued the new type field helmet.

I might say that on the next berth, you probably read about that big ship that France had built prior to World War Two. The Normandie? Before the Germans got to her they brought her over to New York harbor. She was in the next billet. Our understanding what we read about it, they converted her into a troop carrier. Somewhere they claim by using acetylene torches and welding down in, she caught fire. There she was, just like a big fish. Laying on her side. Huge thing! It was a little bit depressing to be getting on one big ship and to see that big ship. We were all looking forward to it, but that was a tragedy. It was a fine ship.

Our equipment was handled by somebody else. We just hauled our personnel down to the docks. Went in from Kilmer by train. The equipment went by different ship. While we were at Kilmer, they loaded us up and took us down to Fort Dix and let us fire rifles on their range. Used Fort Dix rifle range. Didn’t seem like it took very long to get down there. We went in one day. We got to shoot our rifles and see if they’d work. Kilmer was just...we could walk, Bill, the highway down to New Brunswick, New Jersey. There was a house right on the street, with a sign there, “George Washington stayed here overnight.” How I come to remember that. We could get four–hour passes in the evening. So many of us, not everybody, but so many people.

What amazed us fellows was on Sunday morning, they told us no passes. Everything was quarantined in. No leaving. No goofing off. Stay there. By evening we were all ready to load. We’d turned in our bedding, and we had to roll up our mattresses and turn everything in to the Supply. We waited till dark, and they loaded us on trucks and took us over to the railroad and loaded us on the train. After it got good and dark. Took us into New York. Unloaded us, and we walked down the brick streets that were sloped down. Then we got down there, and we were just jam–packed like sardines on small trawlers or something that took us across a body of water.

When we unloaded there we were on a dock. There was stairs and there was the Normandie and there were steps going up into the Queen Elizabeth. Just all the lights were kind of a bluish light and we didn’t want nobody to see us or anything, you know.

We were on there about the third morning and of course they loaded troops around the clock. Enormous ship. We couldn’t understand all that security. On a bright sunny day we backed out at nine o’clock in the morning and go down right in front of everybody and past the Statue of Liberty and bear to the right and went straight out in the Atlantic. We thought we’d sneak out in the night. But they didn’t.

You know how guys will think of everything, you know. When they got out to sea, away from the harbor, you could just feel it. Vibrations, you know. And they was really pouring the fuel to her, and seven minutes she’d go like that, then she’d turn. You could look back and see that wake. Made it white. She’d turn slightly, and she’d go that way. We had to have something to do so we’d watch her wake, and, boy, right on time. They didn’t go in a straight line.

After we got organized, conditions on the troop ship were good. There was confusion the first day out about feeding. We didn’t know...they didn’t do this ahead of time, but they did it after we got on. Like, my group, maybe we’d get a card like a doctor’s appointment card. Mine would be green. Maybe yours in another group, yours would be red. Another’s would be blue. Another guy’s would be white. Well, I don’t know how many different colors was that, and then they had signs on there to the galley where they fed us.

On your card was the eating time. There was no use for me to get in your line with a red card and you had a blue card. There was no use for me to try to go to chow with you because when we got down there was guards at the doors and you just couldn’t get in. So that was confusion for a while. About a day. But it worked out fine once they got accustomed to it, because guys would know they couldn’t get in without the proper card. They said...I don’t know whether this was official or not, but they told us there was around twenty-one thousand of us on there.

In the sleeping quarters I was in, above the door, little room we know, about six feet wide, above the door it said “Accommodations for Two Seamen.” There was twelve G.I.’s shared that room. And likewise with the cot, they’d put instead of one cot on a side, they had six. So that twelve of us could sleep there for twelve hours, and then we had to get out and let twelve other guys get in. When we had to go out, why we could roam the ship, like up on the Promenade Deck. Every place that wasn’t off limits, you know.

I never saw a great deal of seasickness on the Queen Elizabeth. Of course we wasn’t around a lot of either, but boy, goin’ from Liverpool to Oran we was on a British ship, and a lot of the guys got seasick. Small, you know, on the Atlantic at that time. We hit the beaches November the 8th. The Atlantic gets rough that time of year.

You could look over at the other ships and see ’em goin’ like that, you know. You better not watch ’em too long. I was very fortunate that I never got seasick one time. Some of our guys never left their...where we was billeted, from the open deck down one flight of stairs, just like from the ceiling down here, the water level was up there at the ceiling. Then there were guys on below us you know, a deck or two, and it never bothered me a bit. I was very fortunate. I don’t know why.

I’ve kinda got a mental block, but you know there in Scotland where they made this sort of home base for the Queen Mary and the Queen Elizabeth. What is that, the mouth of the Clyde, is the Clyde River there or where is it, Bill? You probably know your geography there. It was like you know where the sea is big and goes inland. Well that’s where they eased her up there and they unloaded us off onto smaller ships.

We ended up at Belfast, Ireland. We went up to Belfast. I was on a small, about a battalion of us just made this little boat, the Princess Mab. It was a British ship, a small ship, the Princess Mab, took us from the Queen Elizabeth up to Belfast. We unloaded on the docks there and we went by truck about twenty mile inland to a little town Antrim. Antrim, Ireland.

The whole regiment was stationed at Antrim. Spread out at different...it was the British Army’s Quonset hut barracks, about two squads to a hut. We went on their rations. They had a central, like a mess hall, and got along pretty good. As I remember breakfast, there was some kind of a, well, it was between a stew and a gravy. I don’t know which one.

September, we must be five days goin’ across and then up there say another day. We must have got up there about the 8th or 9th at Antrim. Then we were through the rest of September up into early oh, it must have been right at the end of the month or a few days up into October.

Then they brought us back to Belfast and we got on the U.S.S. Brazil. It was a nice ship. We got American food on there. We came down to Liverpool, come down along the coast line to Liverpool. Boy, was our eyes gettin’ big. You know Belfast, Ireland, was one of the first major cities that the Germans really bombed. You could see those big buildings.

I know one particular gray, big stone church, the only thing that was left there was the steps, and the entrance doors and the arch. You know, it didn’t look like it was hurt a bit, but then the rest of the building was just a pile of stone. For some reason they bombed Belfast bad, and we came down to Liverpool on that there U.S.S. Brazil. Of course we unloaded on the docks and there was a railroad. There was a railroad and we got on. They loaded us on British trains.

Now I’ll never forget it, you’re probably familiar, but they had the redcaps, you know, the British redcaps. They was the M.P.’s of the British Army. They call ’em redcaps. They was doin’ a good job there gettin’ us on the train. The coaches, you didn’t enter on the ends and go through. The doors opened on each side like a carriage, you know. That was something new to us.

It’d been more comfortable if there’d been say four of us in there, but they put six of us in the compartment with all that paraphernalia. Barracks bag and your field pack and your rifle. It didn’t take us too long to get down there, but we went from the docks, they was takin’ us down to where we was gonna load there at Liverpool on the big ship. They had like great big warehouses or something. Well, I suppose that’s what it was, for freight. But they seemed to be, they’d emptied ’em, and that’s what they run us in there and held us in there. Then there was that waiting period to get loaded on the big ship that was gonna take us to North Africa.

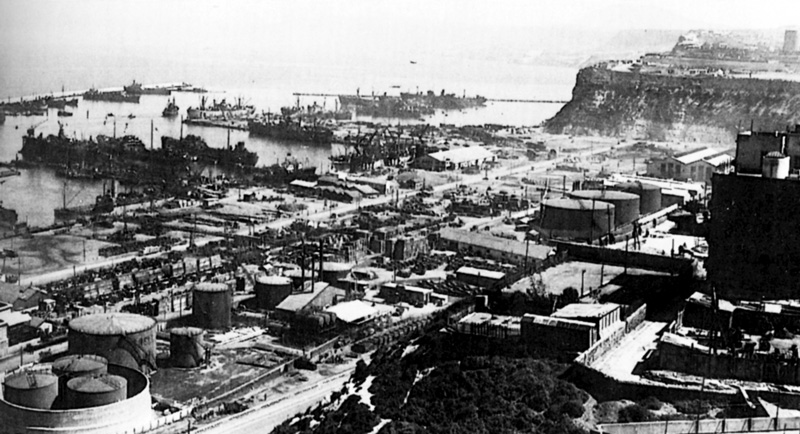

Somebody else was handling our equipment. That’s amazing. Bill, we never saw that until we unloaded and hit the beach in North Africa at Oran and Patton hit over toward Casablanca. Patton, Casablanca, us at Oran, and another unit at Algiers, all at the same time. And here, just in a matter of a day or two, all these ships moved in and started unloading our equipment. Our same trucks, everything. We hadn’t seen these trucks since we’d left Pasadena. Now that’s really bookkeeping, isn’t it? That’s organization!

I’ve read in some of those books where they had special trained people and they loaded every piece of that so it would come out just right. A Company, B Company, it was all marked, you know, stenciled on the bumper. And it was amazing they could do something like that. You’d think that you never would see it again.

It was His Majesty’s...there was a great big plate on the stack right on the main deck...His Majesty’s Letitia. And the Captain, we assumed he was the Captain, he was broad-shouldered, old, looked like an old regular seaman. He had his cap on and his blue uniform with the brass buttons, and every evening, you’d never see him till about four o’clock in the evening. He’d climb that ladder up and there was a catwalk around the stack and the railing. He’d walk around and around that and stand periodically and look out across the ocean. He looked like he’d been at sea a lot of time, never seen him since. There was our whole regiment on that ship plus a lot of guys I didn’t know.

We was in convoy down, out in the Atlantic, and I don’t know just how many days, but it was several days we was in convoy. Right at that particular time the Atlantic was pretty rough and overcast, cloudy, overcast, very little bit of sunshine on the trip. And the seas was rough and on different occasions, one day especially, we had an alert. The seamen appeared from nowhere and started jerkin’ ropes and threw the canvas off of the ash cans on the racks. They were depth charges. They started rollin’ ash cans off and you could hear those things exploding.

The ships, you know they all have their flags across, those flags were just changin’ just like frantic, you know. You could see guys with this semaphore, the flag semaphore, oh the ships would be sometimes closer than from here to Eleanor’s garage. We could almost make out, if you’d been on one and we’d knowed each other you could almost and then other times you’d been oh, four or five hundred yards apart. Usually we was spread out more, but sometimes they’d get pretty close. Different days we went by drums and crates, barrels and things that would make you think, well, something’s happened along here some before we got here. Like something had been sunk.

Oh, gosh I’d say we could see at least twenty ships at the same time. Twenty or thirty. You know there you can see a long way in a ship. When we got down, they had it timed just right and we come right down there to Gibraltar. Well, just like ducks they started a comin’ out of a convoy into a line. Just like a duck we shot through the Strait of Gibraltar.

The weather cleared off and you could see the stars shining. So while each felt a little bit safer, each guy had his own feelings in a situation like that. Felt a little safer when we got into the Mediterranean, but then again we thought sure that the German submarines would just be lined up to shoot us like ducks when daylight come the next morning. But the Navy had taken care of that. They had minesweepers and their patrol boats with sounding devices that they was already ahead of us, I guess. And they was on each side of us.

U.S. and Royal Navy, and I’ve read in some of my books that...you see Patton and his Army came from the States. While we was goin’ from Liverpool, they come across the Atlantic over to Casablanca. Now we never did see ’em, but these writers on it said that our Navy was patrolling out of sight of the convoys and listening for subs, and the subs never sunk a ship. That’s amazing. They never sunk a ship on them convoys. All of ’em got through all right.

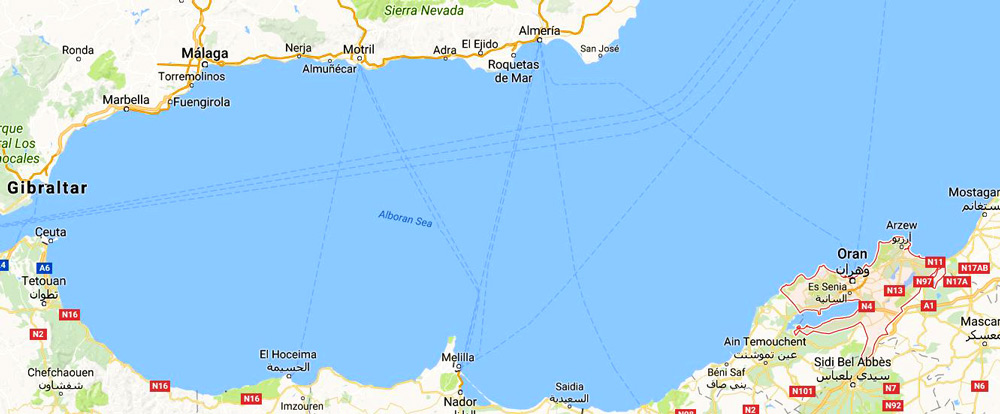

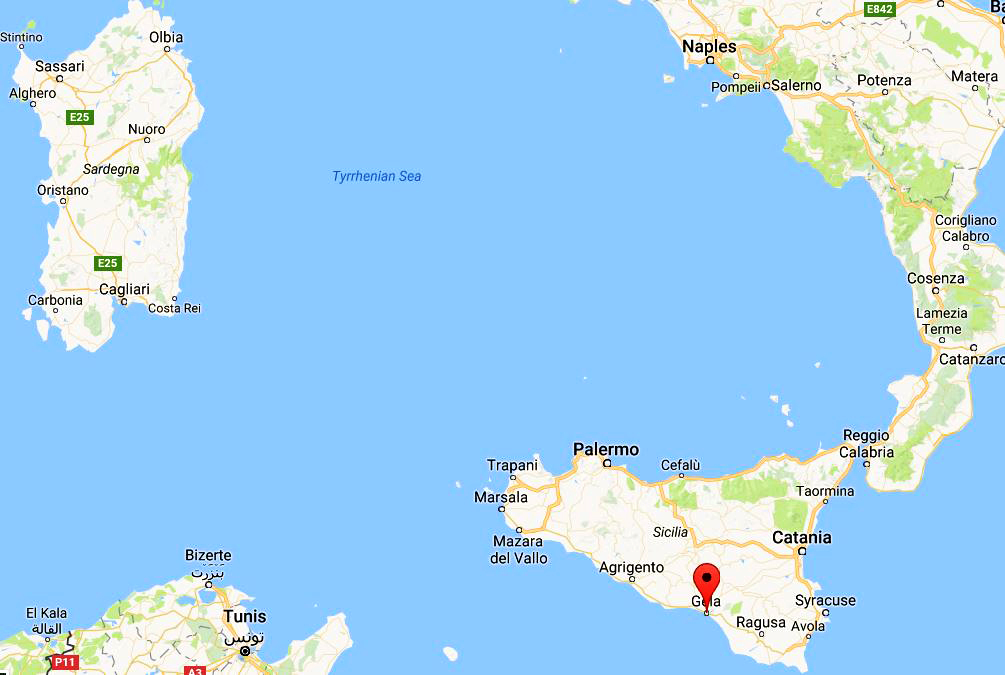

courtesy of Google Maps

Oran is a city in North Africa. It has a pretty big port area, one of the major ports of that part of North Africa. The French Navy was holed up in there, some of the French Navy. The part of the French government that sort of stayed a little bit along with the Nazis and then the Free French, you know...well, there was some of the French Navy in there that wouldn’t come in with us. I say with us, meaning the U.S. forces. They had a fight down there and they had to sink some of their naval ships down there before they’d...that naval commander, the Germans had their finger on him until they had to sink some of their navy down there in Oran Harbor before he would give up to ’em.

We heard some explosions. We’d just got around the Bay, there. We heard terrific explosions at night. They tried to make a run for it, and they got ’em headed off. I think maybe one or two of ’em might have got away.