lon howell

contents—click on a chapter

1—Early life and enlistment

My full name is Alonzo Ellsworth Howell‚ Jr., and I was born in Oak Hill, Ohio, on January 27, 1924. My dad was in Cedar Heights Clay Company, clay and coal. He was half owner and I suppose you’d call him Vice President.

I started school in 1930‚ first grade‚ when the Depression hit. I don’t remember a whole lot about the depression. We never did go hungry. Always raised a big garden and Mom canned and baked all the time. I’ve often told my kids, I said, “I was a freshman in high school before what I knew what store bread was.” You know‚ always home–made bread.

At home there we had Mom and Dad and an adopted sister‚ Gwen. They adopted her when she was very small. The fact is we both went to school together. I think I’m probably seven or eight months older than she is. I attended Oak Hill High School‚ and the subjects I liked best were the math subjects. I played football and basketball. I graduated high school in 1942.

When we graduated I was eighteen. You couldn’t enlist unless your parents would sign your release‚ and they wouldn’t sign it. They wanted me to go to school. Dad was a good friend of Wilbur Stout‚ who was the head geologist at Ohio State University. I was figuring on taking ceramic engineering. So I enrolled that Fall at Ohio State. Then about‚ I think it was sometime in November‚ we get up one morning‚ and I was rooming with a boy by name of Clark Gibbons. It come out in the paper that you could join without your parents’ consent.

So that afternoon we headed to downtown Columbus. We didn’t know what we wanted to enlist in‚ so we decided well‚ we’ll try the Navy first. I said I don’t want to walk. I don’t want nothing to do with the Army. We went in and this recruiter there said‚ “My, with all the math you have‚ would you like to try for the Coast Guard Academy?” That just sounded great to me. I didn’t know anything about it‚ so he told me what all I had to do. Congressman Tom Jenkins endorsed me‚ so I went home.

Tom Jenkins was from Ironton. He was our Congressman. I went home and he wrote the letter‚ and I took it back. Well‚ I had to go take a physical. This was the latter part of November‚ and the doctor found hernia‚ so the Coast Guard said we’ll take care of that for you. They sent me up to the north end of Columbus to the hospital and they operated on me‚ and in the those days you had to lay on your back for two weeks. They wouldn’t let you move. When I got through and recuperated, then they’d frozen enlistments. I couldn’t get in the Academy. They had no more enlistments.

I didn’t know what to do. Dad was on the Board here. Draft Board. He told me‚ “Your number’s coming up pretty quick. If you’re going to enlist you’d better find something.” Ever since I was ten years old, I had asthma. I was allergic to things. I knew I couldn’t pass the physical for the Air Force.

My friend Roll Smith and I‚ we grew up there in Oak Hill‚ and we decided we’d try it. So I was sweating that out. Somebody told me that if you take aspirins they couldn’t detect it‚ so I took aspirins. I wasn’t worried about anything except that physical. Well‚ I passed the mental test, and the physical—I failed it because I was two pounds underweight. That’s hard to believe‚ lookin’ at me today. We was supposed to weigh I think if I remember right‚ 127 pounds and I only weighed 125. The guy told me to go home and eat a lot of bananas and drink chocolate milk and I did and come back in thirty days and I’d gained five pounds. That’s how that all came about.

I don't remember the exact date. I think I’ve got it here. Now this is in‚ July 24th, 1943. Reported at Fort Hayes‚ Columbus‚ Ohio at twelve o’clock and took a physical at three o’clock. At 6:10 we boarded a train and headed for Florida. At 10:30 Monday morning we arrived at Miami Beach‚ Florida‚ for Basic Training.

2—Navigator training

We were the first Air Force cadets to take Basic Training there. We didn’t do anything for two weeks except march and sing songs. Miami Beach. We were right on the beach. Stayed in a hotel. Not an Army base. It was just big hotels. We were the first Air Force cadets to arrive there.

Then we had wooden guns to train with. Take us out there and march us with them wooden guns. I remember just before that, sometime that summer, the Germans had landed four or five people on the east coast around Charleston. Some place on that east coast. The first guard duty I ever pulled was from midnight to four o’clock in the morning with nothing but a wooden club in my hand. We were about a hundred yards apart. Now you talk about a quiet place and scary. Nineteen years old. I just made up my mind if somebody popped at me I was going to throw that thing and take off a runnin’.

Things started happening bout two weeks after that. We had a...I think he was a World War I sergeant. I know I was scared to death of him. He was a John Wayne type. He was a tough old booger and he really put us through it. We learned how to march, and practice how you was supposed to shoot. Then at the end of our stage, we were marched from Miami Beach to what we call now Lauderdale. There was nothin’ there then, up to where they called Tent City. We were up there about a week on the rifle range. That’s where we learned to shoot the machine guns and rifles. That’s the way it was. No matter where we went we didn’t walk. We ran or trotted. We never walked any place.

Tom Harmon was a great University of Michigan football player. He had to bail out of an airplane. He walked I don’t know how many miles through the jungles and got back to camp. He had credited it to the fact that he’d gone through all this great physical training. That’s where they started all that stuff. They really put us through the works. Oh my. They like to killed us. They come up with all the sit–ups and push–ups and the obstacle course. I mean everybody, not only Air Force but all of ’em.

Basic Training lasted from July, I think it was about three months. We were there till September the eighth. Several of the people we started with in Basic Training, I can’t remember all of them. I remember one of them had played ball with the New York Giants, played some football. He had flunked out of cadets and he was going over there in the infantry on the same boat I was on. About a week after he got over there he got killed. First darned combat duty.

At that time you had to have two years of college education to get in the Air Force. Of course you know they couldn’t get recruits fast enough that were qualified, so they took all us young bucks. They sent us to what they called college training detachment. They sent us to a university someplace. I was fortunate enough that I went to Gainesville, to the University of Florida. We entered there September the eighth and we went to class from eight in the morning till six in the evening. Six days a week. They crammed two years of college, mostly math, English and all that. Two years of college work.

We were in Air Force cadets. We was either going to be a bombardier, a pilot (all of us wanted to be pilots), or a navigator. The ones that made it, why that’s what you’d become. You’d either become a pilot, navigator or a bombardier. You’d be an officer.

We were there for let’s see, we were there till January the eleventh. We left the University of Florida to go to San Antonio to be classified. There we had to go through all kinds of more tests. One example I remember very well. They had just like a record, and with your right hand you kept the down here you were turning blocks half way and putting ’em back in the same hole. All those type of tests. On January 20th we took our mental test. I don’t remember everything they put us through. They’d check your coordination, you name it. And so, on the 26th of January that year, I was classified as a navigator.

I entered pre–flight school at San Antonio, Texas, on February the 25th. In that pre–flight school we had to take Morse Code. Boy, you talk about something nerve–wracking. Listening to them dot–dit–dit–dots. And some more gunnery. You used the radio and your Morse Code. You used Morse Code a lot, and then a lot of times you’d use your radio for...well, I used it a lot, especially flying back from overseas, cause that’s the only way I had of navigating. That and shooting sun lines with a sextant. We flew back and that’s all we had. Follow the radio. Of course when you’re in mountains you don’t get a true fix on them. It can be off, so you have to correct that. Then we had all kinds of tables and logarithms for correction.

Actually on navigation, like on a mission, you had to record every five minutes your location. That way it worked pretty good because if you didn’t pick up the wind drift or something, why you’d know when you was off course. In combat we flew, when we went into Germany we flew with what we called flak maps. We would try to dodge the flak guns, those German 88’s, wherever they were heavily concentrated. We'd go around them, zig–zag.

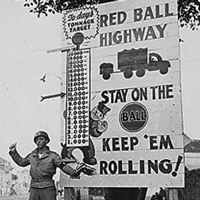

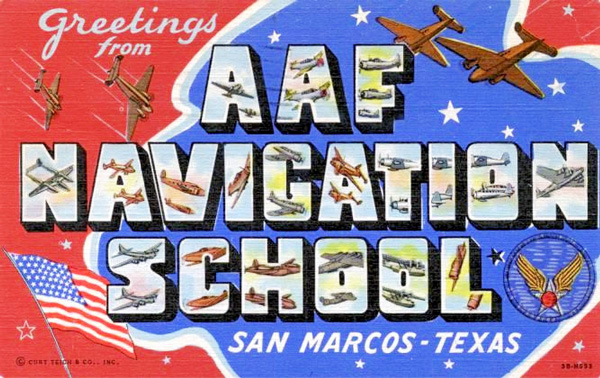

Then from San Antonio we went to San Marcos, Texas to advanced navigation. We went to there approximately in June of that year. I graduated from San Marcos, Texas Army Airfield on the 24th of September, 1944.

The navigation consisted of...we took the earth going celestial and just put it out in space. Where they call it the equator here we call it the equinoxial or something like that up there. That was the hardest thing for me to try to understand. But after we got to flying it, flying by stars and using your sextant, why it come pretty easy.

At San Marcos we flew everyday. We had an instructor, a pilot and three cadets. We flew in what they called a Beechcraft, twin–motored and we’d fly about 10,000 feet. Out of San Marcos we usually flew over the Gulf, El Paso. You had to be within one minute of your estimated time of arrival and you couldn’t be over two miles off course. If you checked all your instruments you didn’t have any trouble with it. We had twenty–four hour watches, and we set ’em by the naval air station, checked ’em. We had these chronometers that you’d set your watch by. If I remember right, if your sextant was off one degree, I forget how many miles off course you’d be off in a thousand. But that’s what happened to, well what was the Air Force General that went down in the Pacific. Doolittle– I believe it was Doolittle. On the takeoff the sextant fell off on the plane. Instead of landing on one of those little islands, why they ended up out in the water.

At San Marcos we flew about every day. Every afternoon. We went to classes of a morning, and then we’d fly till maybe eight, ten in the evening. They really put us through it. We didn’t have much time off. Sunday is all. There must have been I’m guessing three or four hundred of us in the school at San Marcos. Different classes you know, just like senior class, junior class...

I think the percentage, the ones that made it and really wanted to were very fortunate. I think our class, from Basic Training through graduation, there was only about fifteen percent of us made it. For one reason or another they flunked out. Physicals or something. I had one good friend from Cincinnati, Ohio. I often wonder what ever happened to him. On the day of graduation, that morning, they found a copy of a test in his desk. Two hours before graduation they flunked him out. Didn’t even give him a choice. I know that he wasn’t cheating, but they found that test, that paper in his desk.

Everything’s on the honor. Our training was all just taken after West Point, Annapolis. When you go in pre–flight, why you had to sit like this. Braced. You didn’t ask for nothin’. They passed it to you and you had to salute ’em and bow to ’em and all this and that. Of course when you got upperclassman you did a little harassment yourself. I guess that was all part of it. But I enjoyed it. I really did. I’ve often thought maybe I probably would have stayed in. But when we got out they wanted us to give us our choice of gettin’ discharged or go to China as instructors. Well I didn’t want to go over to China and be an instructor. Of course they paid you good money, but we couldn’t stay in. They just had so many at that time.

Norm Crabtree and I went, we left Jackson the same time. Rode the train and everything. Then there was boys from Cleveland. Columbus. We all went to Basic Training together. Then after Basic Training together. After Basic Training is when they started separating us, puttin’ us in different schools. I don’t know how they determined who went where. It was all that testing in San Antonio.

I suppose everybody’s heard of this, but we had been pushed so hard and so hard and we were wanting some free time, so we got to advanced training in San Marcos. It come on the bulletin board we were going to have a party, a Friday night party. Well, that’s what we thought it was. But it was, you get on down on your hands and knees and scrub the floor, that’s what it amounted to. I was never so disappointed in my life. That’s what it was.

I was in San Antonio for six weeks, and we got to go into San Antonio one afternoon. Some guy would screw up one way or another and they didn’t punish one. They punished the whole company. Maybe I did. I don’t know. They had a field out there about the size of a football field and they just lined you up on one end and you’d get on your hands and knees and pick up rocks and put ’em in a bag all the way down. Every hour they’d give you a ten-minute break. Did that on your free time. Somebody’d goof up or do something. My, if they did that today, why they’d be called...those days they didn’t care.

San Marcos Air Force Base, and it was at that time strictly a navigation school. It was about half way between San Antonio and Austin.They had another one out in California, I know. Then the bombardier school, it was not too far from where we were. I can’t think what the name of that place was. We stayed in the usual two–story barracks. Fifteen, twenty, thirty in a billet. They’d come through and they’d flip a quarter on your bed. Now that’s one of the reasons, see, sometimes the whole barracks would be punished. If that quarter didn’t bounce, buddy, they’d...They’d come through with the white gloves and all that jazz.

The Air Force at that time was totally segregated. The only blacks I saw on our base were mess hall, driving trucks. I never did see any black cadets. That’s a funny thing. When we went to Basic Training, I ended up with a bunch of guys from the bayous of Louisiana and Tennessee. In fact I was the only Yankee in the whole bunch. One night in Miami we went out to dinner and we had a black waiter. He’d done an awful nice job. I give him fifty cents and they was going to whip me. They says you take that back. You don’t tip him. That’s their job. So they made me take my fifty cents back.

There was no booze and there were no women. You didn’t have time. You was so tired when you got through of an evening and then they’d have them stinking fire drills at three o’clock in the morning and then peter inspection or whatever you want to call it. Take you out in just nothin’ but a raincoat and then they wanted to check you for syphillis. That was their idea, you know. Had that wherever we went. Some guy’d get the bright idea, call you out at three o’clock in the morning, wanted to check you. They didn’t have a physician there, just somebody there on the base. I think it was just more harrassment than anything else. It’d maybe make you conscious of it, because every base we went to, that’s the first movie show us. Of course when you got a chance you didn’t pay any attention to that, you know. Women were women.

Then you’d have fire drill, and there was four stories of steps. Instead of rolling out for fire drill, I rolled out of bed and rolled under the bottom one. I was on top and I just went under there and went back to sleep and they caught me. So my next pass I had to brush those steps, four–story steps with a toothbrush. Now that is a job. Next time I rolled out for inspection. Couldn’t get by with nothing. What they were trying to instill in us was discipline. I don’t care what you do, if you don’t have discipline, you’re not going to get anything done. Then when you get in combat, that’s where that discipline pays off.

When I graduated from advanced training as a navigator, I was called a flight officer, which is as far as rank’s concerned the same as second lieutenant. I was kind of disgusted with that because I wanted that golden bar. To this day I don’t know why they did it, but three fourths of us that graduated, that’s what we were. When we went overseas, we could go to enlisted man’s club or the officer’s club. We didn’t have to pull guard duty and we got twenty percent overseas pay where the second lieutenants only got ten percent. So financially and every way, shape, and form it was the best deal I ever had.

Being a flight officer instead of a second lieutenant, because I had a lot more privileges and everything. It's just the prestige of it, really, is what you wanted. After we got over there and got in combat, all navigators went to lead squadron. You’d have two deputies on each group and a lead. You’d have a dead reckoning navigator, a radar man and the guy that did the bookwork. So they had three navigators on each plane on the lead crew plus three pilots. Usually the lead plane carried a pilot, co–pilot and then you’d have a command pilot.

The pilot was Lieutenant. Co–pilot was a Lieutenant and I was a Flight Officer and the command pilot was usually a Captain or a Major or maybe higher. I know Jimmy Stewart flew with us once before he became a General. He was a full Colonel. He flew as command pilot once. Most of your gunners, tail gunners, nose gunner, top turret, engineers and all them were usually Sergeants. There was no reason why navigators were flight officers and gunners were sergeants. That's just the way it was. You went to Air Force cadets, then you would become an officer. They didn’t go through near the training we did. The only thing they had to do was learn how to shoot. The engineer had to know all about the plane. Most of ’em, after a few missions, get a promotion. Most of ’em come out oh staff sergeant or better.

3—Crew training

So I graduated September 24, 1944 from San Marcos Air Force Base, Texas as an advanced navigator. We had seven days to get from San Antonio, Texas, to Westover Field, Massachusetts. Then from there we picked up our crews. In other words everybody came in—the bombardiers, the navigators, the gunners. We flew to Charleston, South Carolina air force base. That’s with a full crew to start what they called RTU training, overseas training as a crew.

We all came to together, I suppose the same thing as a football team, and we flew night and day down there. Night missions. Day missions. I know the bombardier had to do a navigation mission, and I had to drop bombs. Also had to learn to shoot the fifty caliber machine gun in the nose. We went through the whole bit before we went overseas.

That training at Charleston Air Force Base. The pilot was a fellow by the name of Adolf Rupp. I never felt so sorry for anybody in my life. His father had fought with the Germans in World War I. They wanted him to stay out, and be a conscientious objector. Which he could have. I was with him way over a year and a half. He never did get a letter from home. He had a first cousin that flew with the German Luftwaffe. We bombed his home town once. He often told me, he said that if it hadn’t been for them sending food, clothing during the Depression over here, they would have never made it. He spoke fluent German. He didn’t come over here ’till he was twelve or thirteen years old.

That’s a funny thing. We were going through the mess hall at Charleston Air Force Base. It was from the German prisoners of war. Boy, that was the best mess hall I’ve ever been in, because they kept it open twenty–two out of twenty–four hours. You could get fresh eggs. That was something. We were going through that chow line one day, and he met a kid that lived next door to him. He went up and talked to him. So Rupp took some pictures of his wife over to him, and his dad. This boy done charcoaled ’em. Beautiful. He was an artist. The next day the FBI come in. I was afraid they were going to kick him off the crew, or what they were going to do with him. Found out it was just a misunderstanding. He didn’t know he wasn’t supposed to do that. They let us go on. He was the commander of the plane, and a good pilot. He was the best as far as I was concerned. He could really fly that thing. Nothin’ bothered him. I’ve tried to locate him. I haven’t seen him since 1945. I can’t find him anyplace. I don’t know where he is. The last time I saw him, we flew back from overseas. We landed at Westover Field, Massachusetts. From there I took a train to Sioux Falls, South Dakota. I don’t know where he went. Haven’t seen nor heard tell of him.

I flew with two pilots while I was in combat. One of them was Rupp and the other was Bob Bluford. He was studying to be a Baptist minister. We always said the Lord’s Prayer before we took off. He would go anyplace with us go to any honky–tonk, but he’d never smoke, he’d never drink, he’d never have nothin’ to do with women. But wherever we wanted to go he’d go with us. That was the kind of guy he was. Everybody just adored him. You know he was a crack pilot.

I looked for him. I figure he lacked two years of seminary to be ordained as a Baptist minister. So I thought, well, we had a reunion at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, and that is the headquarters of the Baptist Church. So I went over there and they didn’t have any Bluford. I just give up. So one night I was just sittin’ at home, and this Second Air Division which I belong to...that was what the B–24’s. See, the Eighth Air Force is made up of three bomb divisions. First and Third were B–17’s and we were the B–24’s. So they started having reunions right after the war. I have a book with all the guys that belonged to the Second Air Division Association. I was sittin’ there one night, watchin’ television, just going through there, and there was Bob Bluford. He’s at Richmond, Virginia, and he’s a doctor. He didn’t become a Baptist minister. If I don’t see him this year in Hilton Head—we’re having a reunion at Hilton Head in November. What I want to do is go over there and get an appointment, and just walk in. May cost thirty, forty, or fifty dollars, and just sit down and see if he remembers me.

We were pretty close, you know. Of course everybody on a B–24, everybody was close in those days. I mean an officer didn't mean nothing other than the fact that we had the rank. Wherever we went, we went as a crew. We didn’t go as enlisted men or officers. In combat you could do it. You didn’t salute anybody under a major. You just ignored them, you know, one big family. You had a job to do and you did it.

I was twenty years old, the third oldest on the crew. The pilot and the co–pilot, and the bombardier. The pilot and the co–pilot was the two older than me. The rest of them were all younger, eighteen or nineteen. The co–pilot Steve was a little older. He might have been twenty–three. I can’t remember Steve’s last name. Steve, but what was his last name...He was an old Texas boy, and before he got into the Air Force, he was in cook’s school. He spent seven years in Texas, five going to school being a cook then he enlisted in the Air Force. Took all of his training and everything in Texas. He was in Texas seven years before he went overseas with us. Heck of a nice guy. I sure hated to fly with him very far. He always had trouble landing. He couldn’t hit that runway. Fortunately, he didn’t have to, other than practice. The co–pilot was just trained as a pilot. They would pick the best ones for pilot, or whatever they needed. See, there’s very few in our class at preflight got to become pilots. I’d say less than one percent. We came to find out that what they needed was navigators and bombardiers. Whatever they needed that’s what they’d send you to school for. I’m sure it’s like everything else.

Tommy Selmon was the bombadier. He was a lieutenant. He was a heck of a guy. He come pretty well through the family from Dallas. In fact, his older brother was one of the top surgeons in the Hospital there in Dallas. Tom was quite a character. I remember before we went overseas while we were in South Carolina, this hurricane come down there. They flew all the bombers to Cuba to get them out of the way of the hurricane. While you were down there, each man was allowed two cases of booze to bring back. That’s bourbon and scotch. I don’t know how many cases we had in our barracks. So we got ready to go overseas. Tommy Selmon threw all of his clothes away. Filled that footlocker with nothing but booze. If they’d ever caught him, he’d still be in the penitentiary. But he did it. He got that stuff to our base. You know we’re there and he wired home for money, an’ they sent him money, and he bought him a whole new outfit.

He’d go down there to prebriefing and you’d think he wasn’t paying a bit of attention to what they was telling him. He get in the plane and go to sleep because he didn’t do anything till they got on the bomb run. That son–of–a–buck. I flew with him, I think, fifteen or seventeen missions, and everyone of ’em was excellent except for one they didn’t get a photograph of. We went down this one airstrip and he put a bomb every fifty foot right down the center of it. I said, “What do you do, sight over your thumb?” He’d get his own wind and corrections and everything while we were airborne. He was an intelligent fellow. That’s just the way he was. He’s still living in Dallas, but I don’t have any idea what he is doing.

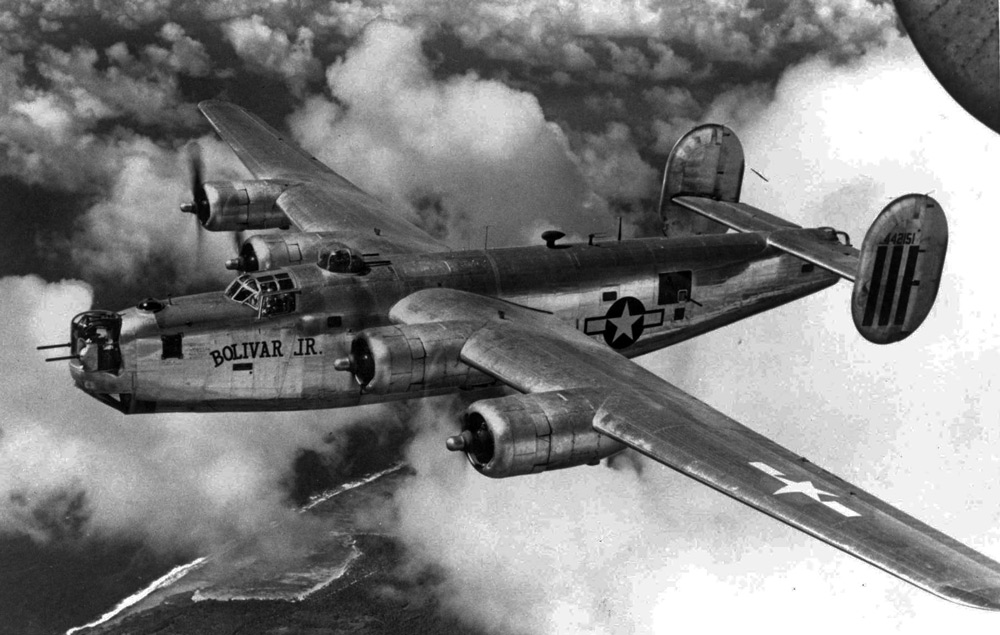

The B–24 had an average of ten crew.

When you handled the stick flying the B–24, you just pulled back. I mean it was manual work. I mean nothin’ easy. I only got ahold of the stick once, and I told Rupp, I don’t know how you can handle, it was worse than driving a truck. The nice thing about the B–24. It had Pratt–Whitney engines, whereas the B–17 had Allison engines, and they could just shoot the tar out of that Pratt–Whitney and it would keep flying, but one bullet in an Allison engine and it would go down, you know. I was kind of P.O.’d, too, when I got in the B–24 instead of the B–17, but after I was in it a while I was sure glad I was. It couldn’t fly as fast and it couldn’t climb as high as a B–17. They usually went about 30,000 feet, we went in at 25,000. It got me there and got me home, so I can’t knock that.

I flew right up in the nose. If I was doing pilotage navigation that day, I usually flew as the nose gunner, too. I’d have my maps up there with me, see, and I could pinpoint myself on the map. I was the only guy in the nose. I was there so I could look around. I remember one time we picked up some target. It was some marshalling yards. I don’t remember where it was, Nuremburg or where. We had these high powered binoculars, and two hundred miles from there I could pick out the trains and the people moving and everything. Clear day, very seldom you had a day like that.

4—Overseas

When we went overseas we went over by boat. We left out of Boston. Then we went to a manpower pool in Blackpool, England. Then from there we went in for replacement crews. When we got to the permanent base, why then we had our own B–24. We went as a crew. The ship we went over on was British. Third largest ship at that time. I think there was eighteen Air Force crews, which was probably 180 men, and 15,000 infantrymen. They took us on first, so we could help pull guard duty with them. You talk about a mess. One big boat. They had them stacked four high.

I was an officer, so we got a cabin. Ordinarily in peacetime, there were four to a cabin. On that trip there were twelve of us in there. We had it made, so to speak. They were sick, and the only thing you had to feed them was that stinking fish. If you could hold your nose it would taste pretty good. Some kind of English fish. You could smell it. Those guys were sick. I never felt so sorry for anybody in my life.

It took us seven days to get over. Left on the twenty–second, got there on the twenty–ninth of December. We arrived at Scotland at Edinburgh. Then they shipped us to Blackpool, England. Just a distribution center, I suppose you’d call it. You know, where you went, and from there they’d determine where you were to be shipped to. We didn’t get our final orders on where to go until Blackpool. The funny part of it was, the Germans had such good spy systems. They’d threaten you within an inch of your life if you told anybody. You don’t repeat anything, you know. When we got to our permanent air base at Attlebridge, England, it was late in the evening and the boys had the radio on.

Axis Sally welcomed us. Told us where our plane was parked, hardstand, the whole works. I don’t know how they did it. That was the funny thing. They knew every move we was makin’. And you know, we tried to keep a secret... Knew what hardstand it was parked at. Where it’s parked.

Attlebridge is a small place right out of Norwich, England. That's what they call East Anglia. North and east, I don’t remember how far, from London. Norwich was kind of like the hub of the wheel. All of our airbases was just right around Norwich. That’s the Second Air Division, where all the B-24’s were situated. Right in there.

The 8th Air Force was out of England. It was made up of three divisions. First, Second, and Third. The First Division and the Third Division were all B–17’s. The Second Division was B–24’s. The mission was to bomb Germany. Plus we had several squadrons of fighter planes. They’d escort us in and escort us out. It was somethin’ to see.

There were several bomber bases. In fact, when we went into a flight pattern like coming in to land, at not very high altitude, you could just look around and see airfields every place. We had short range radar. We called it the Gee-box. When you get on the end of the runway you’d put a bip and a flip like that and that would get you your fix. So when you come back in after you been out on a mission, well, you’d set that in there. Then when those two come right there you’d tell the pilot, “Land. That’s your airfield”. Otherwise, you’d get lost. You’d land everyplace. Lot of times the weather was so bad. That’s the slickest thing I ever saw. It really worked. But it was short. It was the forerunner of what they call LORAN now. Long range navigation.

We were called the 466th Bomb Group. I don’t remember how many planes. You had squadrons and how many squadrons make up a Bomb Group, see. In a maximum effort the Air Force would put out about twelve hundred bombers and eight hundred fighters. I think we had about twelve planes in the squadron. A colonel commanded the squadron. Jacobowitz was ours. I can’t tell you how to spell it. I tell you when I left him his rump was wide as that right there, so when we went back to reunion, and I saw his name on there. I asked this one officer I’d remembered, “Where was Jacobowitz?” He said, “That’s him right over there,” I said, “That’s not the guy I knew.” “Well, that’s him.” So I went over and introduced myself. He was a school teacher before the war. He went to medical school right afterward. He lost all that weight and got down to 140 pounds. I’d say when I saw him in England he weighed 270 or 280 pounds.

He was some colonel. You couldn’t butter up to him. You did your job and you were complimented. If you didn’t you got chewed out. He’d fly once in a while. He’d fly as command pilot once in awhile. But mostly those guys when they became squadron CO’s they’d already finished one tour, maybe two.

They always had the command pilot that’d fly. It’d depend on the pilot. The command pilot usually led the group, the Bomb Group. Each squadron had their own pilot. They didn’t have anybody leading them. Of course we all went in formation. But the head man, he’d go out in the head ship. I think I had three of those I was on. We would go up first, and we had a certain flare. We’d shoot a certain color, and we’d circle. All these planes would get in formation. It would take two hours to get in formation. If the 8th Air Force went in as one big bunch of planes so to speak, well, then they’d have a general or somebody flying as command pilot. Usually you went in as a Group. Each Group would go off to targets.

Hans A. Rupp was the pilot. Alfred Stevenson was the copilot. Alonzo Howell was the navigator. Thomas Selmons was the bombardier. Lee Fuller was the engineer. Martin Goetz was the Martin turret gunner. George Warrington was the nose gunner. George R. Smith was the tail gunner. Harry Hancock was the Sperry ball gunner. Peter Efthin was the radio operator. That crew flew together the first six missions. Then they transferred me to lead squadron which all navigators were sent to.

All navigators and bombardiers went to what they called the lead squadron. The lead squadron was the outfit that led. Either flew as deputy leads or flew as the lead ship, whoever you happened to be flying with. In our Group, the 467th Squadron was the lead squadron. So when we’d take off, there would always be three navigators in every lead ship. That’s deputy leads and the lead, and that’s in each Bomb Group.

Right. If it wasn’t a clear day the guy that did the pencil pushing...dead reckoning, he did all the work. He sat back there and did nothing but...you’d give him fixes and he’d plot the course. He did all the work. If it was a clear day then the guy sitting up in the nose, the pilotage navigator, would do all the work. I mean he’d pinpoint. Pilotage meant he’d just look down at the ground. The maps in England were perfect. If there was a church steeple you would see it. The forest outline, everything was just beautiful. After going to the states from over there, those maps were wonderful. At certain altitude, say at 25,000 feet, you’d look out over your wingtip and look down. We had figures to how far that building to the right of us. See what I mean. That’s the way we’d zig zag into Germany.

Then if it was undercast, why the radar man did it. He took fixes all the time with his radar. I don’t remember how they did do that. Sometimes the Germans would jam them.

When you got on your bomb run, the bombardier, that was his baby. It was on automatic pilot and everything was controlled by the bombsight. That usually lasted ten to fifteen minutes. Not every aircraft had a bombadier. Some of them just toggled off. Whenever the lead ship dropped his bombs he shot a flare. Of course when you got on the bomb run, your bomb bay doors just open, then you just push the toggle switch and they drop. In an emergency the engineer would do it. They bombed off the lead ship, that's the way it worked. The bombers had the bombsights and everything but they didn’t necessarily have to have bombardiers to drop the bombs. The lead ship would just shoot a flare, then when he dropped that flare, bombs away. Everybody would push the toggle switch that released the bombs.

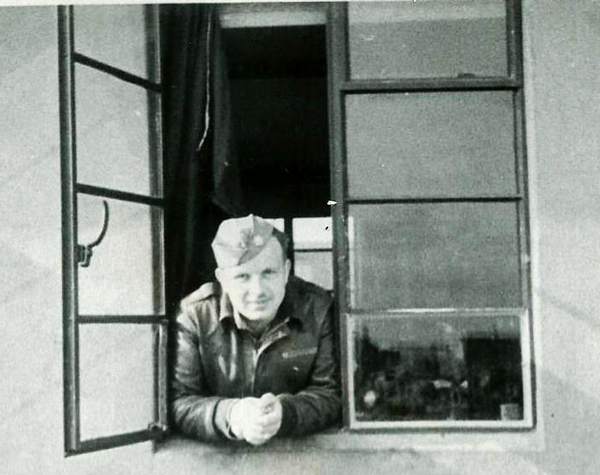

At Attlebridge Air Base we lived in a tar paper shack. About twenty of us to a shack. You had one little pot bellied stove. In our bomb shelter we’d burn, you know, with that little old pot bellied stove. It was cold. We had some pretty smart boys, so this one kid said, “I’ll go down there to them old wrecked B–24’s. I’ll get us some copper.” You weren’t allowed to do that. He did; he wrapped it around that pot–bellied stove. An’ he said we gotta have some coke or something to burn in this. Took a fan and blow it in there.

There were about twenty or twenty–five guys in a shack. The crew would be spread out among several shacks. I was with other navigators or flight officers. Our beds were just straight old bunks. We had to walk about a mile to take a shower. Very few showers you got, really. Just them old things where you had the water up there and you pulled the chain. Have you ever seen one of those? You either got scalded hot, or froze to death, one.

We got pretty good chow. One time a German sub sank the meat boat, and all we had was those English fish and hot dogs for about three weeks. But that was better than C–rations the other guys was eating. Usually in the evening we got a pretty good meal. Hot meal, anyway. Then they’d get you up. Breakfast was about three o’clock in the morning.

You’d get some time off. I believe it was twice a month we got a three day pass. I usually went to London. In the evenings we’d go into Norwich, if the weather got pretty. We’d ride a bicycle into Norwich. We met local girls. A lot of the fellows married English girls. A lot of them.

The Group would fly every day. Not everybody would fly, but the Group went out every day. Seven days a week. Unless like the Battle of the Bulge, the weather was so bad that they couldn’t get off the ground. We bombed every day and the British bombed every night. The one I really remember good is where they was crossing the Rhine River and we were behind Patton. That was a short hop for us. We would fly two missions a day. I forget how many days I went. I think I flew four or five missions, and I think I had five hours of sleep. I forget the pills they’d give you. That was unusual, to fly two missions in a day. More typical was a couple of missions a week.

5—Bombing mission

They got us up around three o’clock in the morning. Then you’d have breakfast. You left early in the morning. We always were pre–dawn. Of course it was the winter time, so we didn’t get daylight until 7:00 or 7:30. Then we’d have breakfast, pick us up in trucks. Ride in the back of trucks to the mess hall. After breakfast each Group went to their briefings. In other words, the navigators went to their briefing, the pilots went to theirs and the gunners went to theirs. In the meantime, they were loading bombs down on the line.

We were assigned to one aircraft, and that aircraft was assigned a spot to park in. What they called hardstands. Just pull it off the runway and park it in there. Concrete. Then we’d take off.

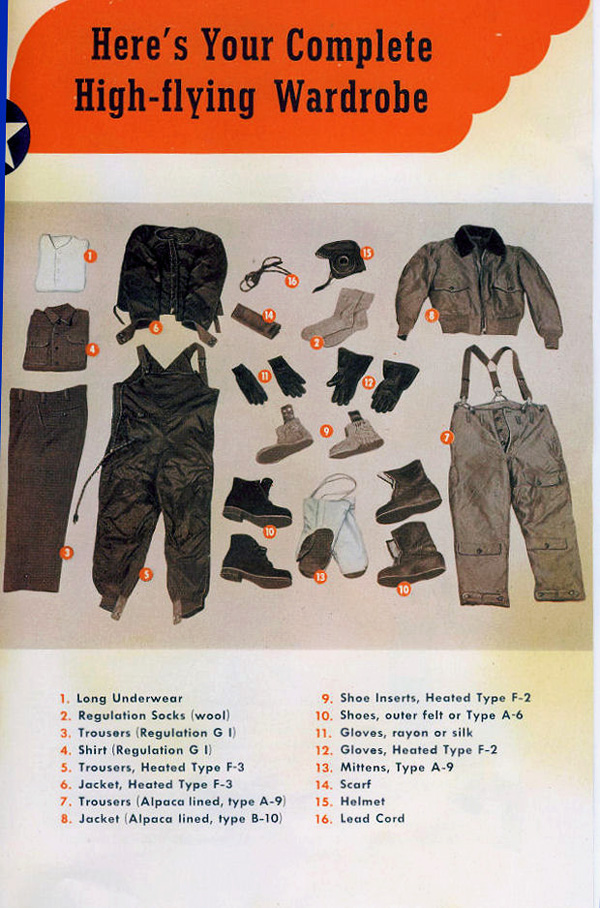

When we got up we would dress in our flying clothes. You didn’t put your electric heated suit on but you had everything else. We wore silk hose under flying boots. The flying boots were fur lined. Then we had an electric suit we put on. We had you know a regular uniform. Then an electric suit over that. Then we’d put our fur lined jacket and pants on. You just plug it in just like an electric blanket. We flew most of the time at sixty below zero. You could see cracks that far in the nose. We didn’t have pressurized cabins. I’d come in many a time, and be nothing but solid ice, clear down to my toes, where you’d exhale the moisture and it would freeze. I’ve seen it sixty below zero.

We had no pressurized cabins, nothing. You went on oxygen. You wore your oxygen mask. Then your fur lined...we had silk gloves under ’em, then silk socks on our feet, you know. Silk ones to retain the heat. That’s just the way it was. I look back now, at the time I don’t suppose I paid any attention to it. We just put it on and went on. Then you had a parachute over all that. Then you used to have flak suits on. That’s to keep shrapnel from hitting you. It’s just heavy armor plate. When you stand on your feet for seven or eight hours, you were pretty well bushed when you got out of that plane. You had no place to sit down.

For breakfast, most of the time you’d get eggs, bacon, ham. Over there mostly ham. Potatoes. On a flight day we finished breakfast at, I’m guessing, four or four–thirty. Then the briefing would usually take half an hour to an hour, depending on where you’re going. On very important missions, somebody from headquarters would come down, and give the coach’s pep talk.

The navigators went to their own briefing. They’d have big maps on the wall. They’d tell us where the mission was that day, and the primary target. Usually they’d give us the wind velocity, temperature, and show us the route in. We usually used what they called flak maps. What that meant was, we would try to dodge the German 88 flak guns. See, they’d move them different places on the railroad. I suppose our intelligence knew where they were, and we’d try to go in around them. The flak guns were marked on the maps. If you’re the navigator, you’re going to be in one of the lead aircraft. They would give us what the camouflaged target would look like. Where they’d taken photographs, and point out where you should go. Give you approximately what the wind would be.

We had maps of all of Germany. They issued them at the briefing. The only maps we carried was little silk maps. Carried those in our boots, just in case. That was the underground route out of there in case you got shot down.

I’d say there were twelve navigators in the briefing room. In our Bomb Group the 787th Squadron was what they called the lead crews. Each lead ship carried three navigators, and each deputy lead ship carried three navigators. You’d have nine right there with each Bomb Group. The commanding officer usually gave the briefing. If it was a very special meeting it would be somebody from Headquarters come down. I remember one time Jimmy Stewart the movie star came down and gave us a pep talk. We were going in to the Ruhr Valley, and I guess it was very important to accomplish what we went after. So he come down and give a talk just like a football coach. You know, pat you on the back, brag on you.

Jimmy Stewart flew a tour in B–17’s and B–24’s. Then he went to Group headquarters. When he flew, he flew as command pilot. I don’t know how often he’d fly after that. He did fly, I suppose, close to fifty, sixty missions. He was a full colonel then. He came out, I think, a Brigadier General. Everybody respected him. Thought the world of him. A lot of them you didn’t, the movie stars. Clark Gable for one. He went through OCS school, and when he graduated they made him a major—he flew one mission as a photographer. That was the end of his military career. Jimmy Stewart—he went right through the whole thing. He didn’t ask for nothing and they didn’t give him nothing. He worked for everything he got. So you know, you respected somebody like that. He’s always been my idol. I think I’ve seen every movie he ever made. He went back to one of our reunions in England, six, seven, maybe ten years ago. He looked at that old B–24. I didn’t see him, but they tell me he said, “My goodness, did we fly in one of those things?” We thought that was a monster ship then. I suppose today if somebody’vd take me up in one, I’d be scared to death.

One mission we went on I remember, was at Hamburg. At that time they was tellin’ how cruel the Germans were, bombing civilians and all this and that. So we went right down the main street of Hamburg. When the guy he says, “Just go right down Main Street.” So that’s what we did. There was no military target to it as far as I know. Most of the time while I was there we were after marshalling yards, oil refineries, air bases, and stuff like that. A marshalling yard is a train station. As far as going right down Main Street, we didn’t think about it. We didn’t even think about it. We knew what the Germans had done to the British, and the French. So it was, you know...you were after them.

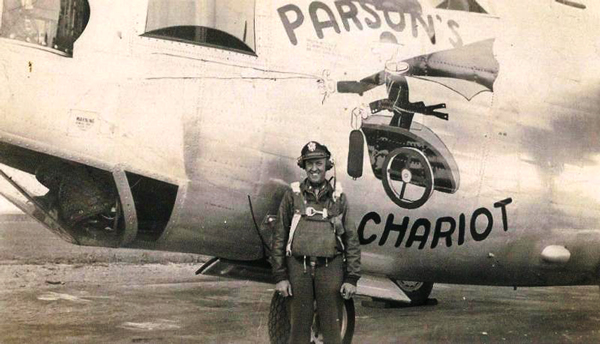

After the briefing room, the ground crews are loading bombs in the bomb bay, and they are fueling the planes and taking care of all that The “Flying Dutchman.” Named it after our pilot, Hans Rupp. It had a picture on it. A Dutchman. We get to the hardstand about five o’clock. From then on we just waited our turn. In our Group there would be about forty planes take off. The lead ship would fly, I think 25,000 feet he’d go up. He’d shoot flares, a certain colored flare—no lights on the planes. Everybody would get in behind him. It would take about two hours to get in formation. If it was an all–out effort, with the B–17’s and the B–24’s, you’d probably have twelve hundred bombers in the air.

That’s the first mission I went on, and I was just too fascinated looking around to do any navigation. Fact is, you should have in your log a location every five minutes. You take an eight hour mission, or six hours, that’s a lot of logs. I think I had five. Five notations. When we came in to debriefing why then they asked me all these questions. Did you see planes shot down? I don't know what all they asked me. You get up there and they start talkin’ the questions to you. “Why did you do this?” and “Why did you do that?”. That first mission taught me a lot. From then on I was all business. I didn’t look at all those planes.

That’s the most fascinating thing I’ve ever seen in my life. Everyplace you could see was nothing but fighters and bombers. I think we had six or seven hundred fighters with us that day. Close to twelve hundred bombers, that’s all you could see—going into Germany. I can remember where we were headed. Berlin. I was a little shaky, because the old timers in the barracks told me that’s where it was going. They were just guessing. We left the barracks and they said, “You won’t be coming back, cause that flak is terrible over there. We’ll just take your blankets now.” As a young kid, that kind of worried you a little bit, you know. Then after you got in the air, why it was just like a football game. The first time you get hit, then you forget about it.

The worst part I found out about it...as long as we continued flying it didn’t bother me. But boy, they give you R & R. Rest, you know, for a week or so? Then you had to start back again after that. It really bothered me. I don’t know why, but it did. Everybody said the same thing. As long as you were busy, you were so keyed up and tense that you didn’t have time to think about anything else.

Getting back to the mission, it took about four hours to fly to Berlin. We usually went at 25,000 feet. We were carrying what they called RDX bombs. Which is the most sensitive bomb there is. We got all the way to Berlin and they told us not to drop our bombs, because we didn’t have any fighter escort. So come on back home. So that’s what we did. When we got back our base, our base was closed in. Weathered in. They sent us to a Canadian base, or an English base.

The way the English would land, one plane come in at a time. When he cleared the runway, another would come in. The way the Americans did, there would be three on the runway at one time. That lead ship peeled off, just like a fighter and come on in. That’s what we did. But the runway was a little short, and the pilot overshot it. He had to put on his brakes, and he tore the nosewheel out from under it. We just went a scootin’ down on the ground, and we had all those bombs on there. We didn’t know we were supposed to drop them in the North Sea.

Nobody could understand it. After we were already there, why not drop them? Of course they couldn’t drop them on Belgium or anyplace like that. Because that’s where most of the guys came out with the underground, so they didn’t want to make them mad. So the only logical place to drop them rather than bring them home was to drop them in the North Sea. Nobody could imagine not dropping them on Germany, but that’s the way it worked. Whoever was on that mission that day, that’s right. They come back. Landing with a full bomb load was a mistake. They were very sensitive bombs. So, blew the nosewheel out, and got it fixed and took off.

Another mission we were on. We might have been going to Nuremburg that day. Anyway we were down in southern France going into the Alps into Germany and coming back, why we had an old war weary plane that day. The gas gauge said it was out of gas. This was southern France. Still a lot of Germans down there. The pilot called me and said, “Where’s the landing field?” I said, “Well, I don’t have any landing fields. I have none. No maps or nothing down in this part of the country.” So, we just started climbing. I think we got up to ten thousand feet and he was a hollerin’ “Mayday. Mayday.” We were all ready to bail out. I was back on the catwalk and everything. As soon as he opened those bomb bay doors we was going.

There was a medium bomber base just ahead of us. We were right over it. You know, that was the only airbase wasn’t closed in in all of Europe. We were right over it. We landed and they said we had three minutes of gas left. We was right close to Lyons, France, and we decided we’d go in town. Because we weren’t going to be back the next day anyway. So we got down there at the guard, and he said, “You’d better take your gun with you. Them little ol’ French girls will stab you guys in the back. They hate your guts.” I said, “Well, I don’t want to see Lyons that bad, if I have to take my gun with me.” I guess they just bombed hell of it, you know, when the Germans was there.

We flew every day, either in combat or on practice missions. I was over there from December ’till June, and I flew seventeen lead missions. That’s what I got credit for in combat. Now, we flew gas into Patton or down in France but we didn’t get credit for none of that stuff. That was worse than combat. You had them old gas tanks in your bomb bay. One little old leak, and a cigarette, or there somebody smoking, or a spark, why, it would blow you up. Then we went in at low altitude. It was scary. I felt scared.

If you remember, he’d have been in Berlin long before the Russians if they had given him the gas and ammunition that he needed. So he ran out of gas. The quick way to get it to him was to fly it to him. We delivered the gas around Lyons, France. Just had big gas tanks in the bomb bay. Rough handling and leaking. Sparks, you know. Your four motors. Even if your superchargers charging your batteries would over charge, they could cause an explosion. In fact, I had a good friend, that’s what killed him in a B–17. Blew up at ten thousand feet. Superchargers over charged it, and that created hydrogen. A spark and that was the end of it. Blew up.

That’s some of the things you hear about and you worried about. So many things could happen. Most of the guys, the way they looked at it, and I know I did...if the bullet’s got your number on it, don’t worry about it. It will get you. If it don’t, why forget it. Twenty–five missions and you were supposed to go home. Twenty–five missions, and that was about it. That’s all I guess you could take, mentally or whatever. You were under stress the whole time. You had to be on your toes looking for fighters. We called them bandits. Trying to keep in formation, and bad weather, so you were under quite a stress all the time. I’m sure that’s one of the reasons they give you that drink when you land. To relax you.

Anti–aircraft flak would sound just about like hail hitting on a tin roof. Just chunks of metal. Sometimes the shells would explode and they’d be close and stuff coming out of them. Guys would report that as an airplane being shot down. But, just thousands of pieces. It’d have to be pretty close to get hit, you know. We got some shrapnel, back in the waist, but I don’t know how close really they were. Our crew did not take any hits. We were very fortunate. We had one fellow that flew with us and he was a former navigator. He got hit up in the nose, where navigators rode, in one leg. He got it repaired and he came back. He was just going to fly as a waist gunner to get the one or two missions in his tour. He wouldn’t fly in the nose. He flew in the waist. The day we got flak, he got hit in the other leg. So that ended his tour. You flew after you healed up. That fellow wasn’t serious, you know. He just got shot in the leg. That’s what happened to him, but whether it was his own doings, wanting to stay—I don’t think it was.

Just like this boy that was in our barracks. He was there before I got there and I know he was there four or five months after. Doing nothing, just laying there. One night he’d come in and he’d preach the Bible to you. The next night he come in and he’d be drunker than a monkey. That’s just the way his personality was. They didn’t do anything to him. He didn’t hurt anybody. Why they didn’t send him home I don’t know.

About the only time we’d see German fighters would be if you had to go home by yourself. If you got hit and you had to abort. One time, we were around Hamburg and our plane had just had the four engines rebuilt, put back in. Two of them had the oil line put in backwards, or something. Three fourths of the way into the target we lost two motors. So we had to come home. We were afraid we would get into fighters, but we had four or five fighter escorts to bring us home. We made it back in good shape with those two motors.

Fear. If I was up in the nose doing pilotage, I was probably trying to get the machine gun around to shoot at the fighters if I saw them. At that time you didn’t think anything about it. Now, after it was over with, you landed. If it was somebody you knew real well, why then you begin to think about it. That’s what we were trained to do and that’s what we did. It was either your life or theirs. If you’re going to shoot, I’d rather shoot the German down than to have him shoot me down. I had occasion to shoot at fighters, but I never could hit one of them. I couldn’t get that thing around fast enough. I wasn’t trained as a gunner, but I sure tried.

You remember you have a nose gunner, a top turret gunner, two waist gunners, and you got a bottom gunner, and you got a tail gunner. Now this is each bomber. What they did, when the bandits come in, they’d just lay down a barrage. They’d just lay down a barrage, up and down, below, side and everyplace. If he come in there, why then he was going to run into one of those bullets. They was going to get him. You know as far as trying to say you shot one down with a fifty caliber, it would have to be pure luck, unless he’s coming right at you.

I think we shot too many of our own planes down. Cause, you know, you only had a split second to identify an airplane. I remember, when I went to Group headquarters and they sent me over to the lead squadron, I had to go down there for an interview because they were going to give me a promotion from flight officer to lieutenant. I don’t know which colonel it was, one of them passed me, and he said, “Do you know the difference between American fighters and German fighters?” I said, “Yes, sir”, and he said, “You better go back there and tell your gunners. We're getting too many of our boys shot down.” See, what was happening was the fighter was probably chasing the German going after the bombers. The guys say, “Bandits” and they just start shooting. They didn’t identify them quick enough. You just had a split second. I mean when we were going through cadets, it was just like that. The German fighters there, you had to identify them.

You had no feelings toward the enemy pilots. Just the enemy, no feelings, period.

I shot at a jet one time. I was probably five miles behind him. I kind of got a thrill out of it, I guess. I couldn't get the turret around. He was just too fast. Well, they’d come up and you could see them out there. You could see the outline of the pilot’s head. Of course, our fighters couldn't touch him. When they come in he’d just go straight up, and just run off and leave him. I saw two or three of those.

If the Germans had jets sooner, it would have been a problem for us. I got this war, Eisenhower war years book, that his grandson wrote. That’s quite some book. If Hitler had listened to a few of his generals, instead of doing things his way, the war would have come out a lot different. They was so far ahead of us in everything, technically, you know. Of course the Air Force went in and destroyed all that.

We had escorts all the way. In enemy territory. They’d take us on in. They were P-51's and P-47's. They flew at first from England, then after they got in France...when I got there, they were flying out of airbases in France. They put the fighters farther forward than the bombers, on account of the fuel situation. They also had B–26 medium bomber groups there in France. That was bombing Germany.

We never had it happen, but the Germans would capture these bombers and they’d pick you up and fly home with you. Then when you were starting to land, that’s when they'd open up, with your own Bomb Group. That was one of the things you always tried to watch out for. Whether it was a B–17, a fighter, or a B–24. They’d man those planes, get them running, and tail in with you. Then after you were in your landing pattern, it was just like ducks on the water. You could get shot down. So they didn’t miss any tricks. They knew them all. They really did.

Beautiful camoflage. I forget how many times they went to the port of Hamburg and thought they bombed it. And all they were bombing was water. You know, you couldn’t pick it up, or they didn’t pick it up.

We lost a lot of crews on the last mission out of our Group. I don’t remember how many was shot down. Last mission we flew. One fellow there in the barracks decided he couldn’t go any more. He was a copilot. He went beserk. He was on a mission and they tell me that he just started beating over the head of the pilot and everything else with his steel hat. He just went crazy. I had a good friend of mine, a bombardier, twenty years old. He was grounded because he was an alcoholic.

When you were on R & R, you were always worried about being shot down. That was always on your mind. I think too when you was on R & R why you'd probably think of the folks back home. Whenever you were busy you didn’t have time to think of that. They kept us on the go pretty much. A lot of fun. A lot of hard work, and a lot of scary times. I look back now, it all seems like a dream.

We went to Bielafeld. Bombed Bielafeld, Germany. Went after a bridge there. Went to Hamburg. Nuremburg two or three times. Down in Yugoslavia. Southern France, at Bordeaux. Dropped gas bombs we called them down there. The German army had gone, but they were still entrenched in the city. So they dropped these gas bombs on them. If it didn’t burn them it would give off carbon monoxide. We used gas, so to speak. Not much difference between carbon monoxide and mustard gas, really.

We went into the Ruhr Valley. After Patton crossed the Rhine River, our Bomb Group was attached to him. In other words, we bombed ahead of him all the time. I know one time we bombed too close to him and that night when we got in there was a big message on the bulletin board says “Keep your goddamned Air Force there—when I want you, I’ll call you!” Signed General Patton. That’s just the way he was.

We’d land several times. When you land with him, you’d put your hard hat on. That’s the only time we ever wore a hard hat, or a helmet. You know, a steel helmet. Because the MP’s would make you do it.

Probably sixteen hours you were up, when you were flying a mission. The next day if you wasn’t flying, then you’d go up on a practice mission. That was their theory. Practice makes perfect. You just practice, practice, practice. Sometimes it wouldn’t be a navigation mission. Sometimes it would just be a pilot, landings and takeoffs.

We flew what they called low altitude missions and I mean right on the tree tops. Where before they’d want you to fly at altitude. Some of the crews flew directly from England to the Pacific. I don’t know whether they did that over there or not. We practiced a lot of those about everyday. Go out in the English countryside, and scare the farmers to death. I remember one time, this guy was putting silage in his silo. Rupp just went over and back, and then he feathered his props. That makes, just like those truckers...you know that racket they make when they’re trying to slow their truck down with its motor? That's about what those B–24’s did. An’ he threw that Englishman off his wagon. They had too much of that, they made them quit it.

But you know, everybody is young and they like to do those things, that was thrilling. Buzz fields. I remember Shorty Lewis, the undertaker. Edward Lewis down in Oak Hill. He was with a fighter squadron over there. Mail was always censored, so when we were on practice missions I’d make up a little parachute. I’d wrap a message in with a bar of soap or something. Rupp would call into the tower and would want to know if we could come in and check our altimeter—that means we was going to buzz their field. If it was all clear they’d let us buzz their field. So he just opened the bomb bay I’d throw the little parachute out and Shorty would pick it up. I’d send him messages all the time.

We took passengers after the war was over. Ground personel who had never been there. Just let them see, fly over and let them see the damage.

We all had to take our Air Force patches off, so they wouldn’t know we was Air Force. I had an intellegence officer over at Rotary in Oak Hill, after that. He gave a talk. I went up to talk to him, and he told me that every city with a population of ten thousand or over in Germany was eighty percent destroyed. Every city with a population of ten thousand or over. You must remember the Fifteenth was bombing them out of Italy, and the English was bombing every night. What we missed, the tanks and the cannon got, so they just totally destroyed it. It was really something.

How accurate was our bombing? If we were going to bomb Main Street in Jackson, if we got within five hundred feet of it, that was excellent. We didn’t have any pinpoint accuracy, with the bombs and things in those days. Suppose we were going to bomb the Cambrian Hotel there. 25,000 feet. If we could hit within five hundred feet, that was considered an excellent mission. See, years ago I was in Dayton or someplace, I met the Thunderbirds. They put on, at one of the reunions, a show for us. He said, “You know what we can do today? At 52,000 feet, we can take a bomb and split a dime in two.”

We could, for example, knock out a bridge. I saw one mission. I was telling you about this Tommy Selman—he was uncanny. There was an airstrip, but I don’t know where it was. He put those bombs every fifty feet right down the center of that airstrip. I don’t believe you could have measured them side to side—every one of them fifty feet apart. You could see it just as pretty in those pictures. Sometimes I suppose the wind had a lot to do with it. You calibrate the wind and your plane, it can affect your bombs on the way down, too.

At that time we did not think about the damage we were doing with our bombs. Since then I’ve thought about it. I often thought, what if it had been America. But at that time there was such hatred—and the Germans were so mean—the Nazis. Not the German people. You heard of all this stuff and what they'd done—just like the Japanese, you know.

Now you meet them, and you go back. I went back to Germany. Nicest people in the world. At that time, especially Hitler, he had them, they were really wild people. They didn’t care. Well, it was either you do it or they do it. I’ve often thought that what if Hitler had got the atomic bomb instead of us.

Was the B–24 a good weapon? I don't know about the Germans, their Stuka dive bomber was an awful good plane, and their Messerschmitt. No, I was disappointed when I got in B–24’s, cause the B–17’s was the glory boys. That’s what I wanted in. But after it was all over, said and done, I think the B–24 was a great bomber. I think it was one of the best. You wouldn’t believe what a beating and shooting those would take and still fly. I’ve seen those things come in and land, and just be full of holes. They had that good Pratt & Whitney engine. They could shoot holes through it and it would still fly. Where the B–17, that Allison engine, that didn’t take much to knock one of them out.

I don’t know as we were any better than the British, but I think we did a better job of bombing than they did, just because we bombed in daylight. The British went in at night. One plane would fly in the prop stream behind the other. They didn’t go in as a group. They thought it was probably safer for them if nobody could see to shoot them. That was their attitude. You’ve seen these vapor trails in airplanes. At certain altitudes under certain weather conditions, you’re going to get into them. We’d be flying in Germany, with vapor trails. The Germans knew this as well as we did, at what altitude we were flying.

Down in the Ruhr Valley it was rough. We called them sharpshooters. They’d pick out a certain bomber, and they’d shoot it out of the air. Most of the time it was just a barrage. They had women, little boys, just shooting the guns.

We were trying to bomb factories, mostly. Those were tough targets, even in the latter part of the war. They was still trying to keep producing.

I never actually saw any German soldiers. I saw a lot of prisoners of war. Our mess hall in Charleston, South Carolina, was run by prisoners of war. They didn’t look any different from we did. Young boys, but they wasn’t the hard core Germans. The SS troops. They were just forced in the Army to fight like we were, I suppose.

6—Time off

We had time off in the evening. If the weather was pretty, maybe we’d ride a bicycle into Norwich to a pub or something. About two or three miles away, if I remember. But mostly we played cards. We’d play gin rummy, bridge. Then if it was pretty during the day and you didn’t have anything, you’d play ball. Baseball, softball, something. We didn’t play much softball. Most of the time the weather was so bad you couldn’t get out and do those things. When I was there even when we left in June to come home, we wore heavy leather coats, fur lined. It was that cold air, you know. Mostly we played bridge. We played pool. They didn’t call it pool. What’d they call it? Snooker. I mostly played bridge with some fellow who was a real good bridge player. We won quite a bit of money. Then there was a lot of guys who played poker. Penny ante poker.

Usually after you had your pass, we ended up going to London. You didn’t have enough money to go next time until pay day. So you go back and you play poker to see...whoever won the money, they’d go on the next leave.

I wasn’t there for the hundred mission party, but I was there for the two hundred mission party. You couldn’t get off the base for three days. You didn’t fly, you didn’t do anything. They had all kinds of things but the funniest thing...they had a bicyle race. You drink two beers if I remember right and then you’d ride to first base. Then they had a john there. Two more beers. First to second was maybe a hundred yards or so. When they come into home plate, now that was something. And you could buy a glass of champagne for twenty cents.

The two hundred mission party. Every hundred missions they’d have a party. Everybody on the base. You couldn’t get off. But they’d sneak girls in. I know some of them boys had girls in there two or three weeks afterwards. They’d put GI clothes on them so nobody would catch them. Some of those enlisted boys. I think part of our crew was involved in that. Nobody turned them in, you know.

Girls were pretty available. In London they called them English commandos. Prostitutes, I suppose. A lot of them married, married women, you know. Their husbands...a lot of those guys, their husbands from England had been gone for seven years. They were in Australia, the Pacific, fighting. Women were no problem really, none whatsoever. When we got to London we would mostly hunt girls. We had a place they called The Nut–House. All of us went there. They had an American band. They’d play jazz an’ music. That’s where we always ended up. You had to go down into the basement. Everything was blacked out, you see. Once in a while one of those V-2 rockets would come over and shake you up a little bit.

Most of the time we went to Norwich. It was close. I would feel just as welcome right now going to Norwich, England, as I would going to Oak Hill. Once they find out you was there, why they just open up. Just so friendly and nice. Fact is, Sue, my second wife, she’s never been there, but we hope to go back next year. We’re going to have a reunion over there in July next year.

I went to church about every Sunday, if I wasn’t flying. This one pilot I flew with, I was telling you about, the name of Bob Bluford, was studying to be a Baptist minister. We'd always say the Lord’s Prayer every morning before we took off. He had a good crew. He was one heck of a nice fellow. That helps you. Everybody carried a Bible. The vest Bible my Sunday school teacher gave me when I was ten or twelve years old, I guess. I carried that in my vest pocket. I never did see an atheist, I'll tell you that. I never did run across any.

All of the airmen I knew were patriotic people. That Hans Rupp, he never got one letter the whole time I was with him from home. They wanted him to go in as a conscientious objector. Which he could have, because his father fought with the Germans in World War I. One of his cousins was with the Luftwaffe. He defied them and he was the best pilot I ever flew with. He could really handle that plane.

How important was alcohol? I suppose most everybody drank. When you wasn’t flying. One thing that would restrict you, because we didn’t have pressurized cabins. If you get that alcohol, pop, and you get that in your joints...the gas, you get what they call the bends. I guess it is painful and they wouldn’t abort a mission for you. You’d have to suffer it out. They’d tell you if you were going to fly, just don’t drink that stuff. Anything like that. I took them at their word.

We had a lot of accidents on bicycles. Fact is, I had a bombardier, boy out of Boston I flew with. They grounded him. Said he was an alcoholic. Twenty years old. He rode a bicycle drunk and broke his shoulder. That’s the last I’ve ever seen of him. I don’t know what happened to him. Collant. That boy's name was Collant.

But that’s the first thing they give you when you get back on a mission. They take you in and give you, about a glass about that high of one hundred proof belt of whiskey. You know, you’ve gone sixteen, seventeen hours with nothing in your stomach. You drink that, why, you go in there and they start debriefing you and asking what you saw. Why, they saw things that never existed. I never did understand why they did that. Then they’d give you sandwiches. After about an hour, they’d take you into this big briefing room. If the navigators had messed up, they’d get you up there and make you explain why you did this and why you did that. Then they’d have movies. They always took movies, to critique your mission. How you can improve.

We were given enough notice so that we could drink in the evening and be ready by flight time. Plenty of time. One time we just got back from London, and we had had a wild party. We wasn’t supposed to fly and we did. First thing you do is put your oxygen mask on. That will revive you right now. Then they had these benadryl pills to keep you awake. They’ll hand those out to you. You’re ready to go.

I suppose they would ground you if they caught you drunk, but I never did see anybody drunk. Might have a hangover or a headache or something. Rupp didn’t drink and Bluford didn’t drink. Maybe have a beer but that’s about it. I don’t know of any of those boys I ever did see, that was drunk on a mission or drinking. You couldn’t take it. I mean your body’d get those bends and it is something. I mean it is painful. We didn’t have anything else to do, why yes, you’d drink. You’d go to the taverns, the pubs.

American servicemen had money and also had soap and cigarettes. Soap and cigarettes would get you just about anything over there. We had a little Jewish navigator, never could figure out who he knew how he got a pass. But he’d buy up all the soap and cigarettes he could and he’d go to France. He’d get three or four days off. Last time I looked in his foot locker, he had dollar bills stacked that high. Ten dollars. Twenty dollars. Take them over there and put them on the black market. I don’t know whether he sold them to GIs or where he sold them. He never would tell us.

Glenn Miller was at our base just two or three weeks before he was killed. His band was. They had the big bands that would come in there and they would perform and put on a show. I forget what the date was, but just two or three weeks before I got to the base, he was there. He was going over, I suppose in France, to arrange for a tour over there, and they just went in a small plane, three of them. As far as we know, they went down in the North Sea. Last time anybody ever see them.

We had our officer’s club and the enlisted men had their own club. We saw our enlisted crew when we were flying and when we were on leave. Flying or going on leave. We’d all go on leave together, buddy around together. We didn’t pay any attention to rank. We didn’t even salute in England, unless he was a major. We were just fortunate to have the rank, but as far as I was concerned each man’s job on that plane was important as the other. They’d call us lieutenants, and we’d just call them by their names. Rank really didn’t mean anything, as far as all the crews I’m sure, because you were just a well knit...your life might depend on each other so it was more of a buddy–buddy deal. We trained together. We flew together. We went on leave and everything, you know, did everything together.

7—Back home

I had seventeen missions up to V-E Day in May of 1945. After V–E Day I stayed about a month. From Attlebridge, England, we flew to Valley, Wales. There were fifty–two planes took off. We stayed there all night and then the next day we went to Iceland. We were in there for a night. Then we took off from Iceland for Goose Bay, Labrador. From Goose Bay, Labrador, we flew to Westover Field, Massachusetts. Each airplane had about twenty men on board, including crew and ground personnel. We were demobilizing our Bomber Groups in England.

From Westover we got our thirty–day leave. I came home and got married July 8. Then when I went back, we went to Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Then from there they shipped twenty–two navigators to Great Falls, Montana. It was an Air Force base, but I think it was more than anything else just a staging area. To ship airmen to other places from there.

Our understanding was we were going to go as replacement crews in B–29's in the South Pacific. Of course the war ended before we ever got a chance to go. I don’t know as there was any special training for the B–29. I think most of our training in Great Falls was they didn’t have enough for us to do. To try to keep us busy, they made us take paratroop training. We still had to fly our four hours a month to keep our flight pay.

I assume that Great Falls was the stepping–off point for flying planes to the South Pacific. In other words, they would probably have been some B–29 planes come in to Great Falls, Montana, and from there we would have formed as a crew and went to Alaska and then flew over. There were twenty–two navigators at Sioux Falls. In the South Pacific they didn’t fly like we did in Europe. They flew a lot of single missions, so I assume each bomber would have a navigator.

We went through parachute school as far as jumping off the high pole. We never did have to parachute, but that was scary enough. I don’t how high it was, but they had a big cable, and you get up on this platform and you jump. The cable was loose to simulate the jerking when the parachute opened. Then you just come a sailing down this cable, and they would jerk the rip cord, and you would just go flying. It was teaching you how to roll when you hit. I expect it was two stories, anyway. Or better. Looked a lot higher than that when you got up there the first time. You step off or they throw you off. The first time I landed on my heels instead of the balls of my feet. Roll, and after you caught on to it it was simple. You know, you had a hold of the air and as soon as you hit, you hit on the balls of your feet, and then just roll like a ball.

After the Pacific war did end, you got discharged for your points. A lot of the guys had been in the South Pacific that come in there and they had a lot more points than we did. So they get discharged first. We got relieved in, I believe it was November, October. I went home in November of 1945 as a lieutenant in the Army Air Corps.

I was in a little less than three years. Then they kept me at least on reserve status until 1955. I didn’t get my discharge papers until 1955. I got a stack of mail that high wanting me to come back in during the Korean War, but they never did order me to. They just asked me to and I never did accept. I had a family to rear. Married, and had a business.

I entered Ohio State in January of ’46 and I was up there the rest of that year, and Dad got sick and I had to go home. I studied Engineering. I wanted to be a ceramic engineer. That’s back in Oak Hill at the brick plant, and clay mines. Things just didn’t work out, because after Dad got sick, then Betty’s mother got cancer, and she died in 1948. We inherited her younger brother, Dick, he was six, and her younger sister, so we couldn’t afford to go to school then. I got in the explosives business and started working for my dad. Then eventually I bought a drill, and drilled, myself. Got into drilling and blasting, and I stayed in that for thirty years. It was about ’75 or ’76 before I got out of that then went to work for Atlas.

I learned explosives the hard way. Of course I had a lot of nice people, and experts help me with Hercules. In those days they had an expert for everything. If you wanted to blow a house down, they’d send a man in to do that. Or shoot a ditch, they’d do that. Or coal mines. They’d always stay there in the Cambrian. They’d spend two weeks at a time. They’d just travel with me, then they had schools to go to all the time.

That’s how I served my apprentice, they wouldn’t turn me loose. I just didn’t go out there the first time. I did the hard work. I loaded the holes under their supervision, you know. I probably did that for three or four years. Then we had certain formulas we used, like in the strip mine. Depending on the rock formation, whether it was soft, hard, or what, and just ask them if you wanted it shot, blasted away, or just shook up or however way you wanted it. Then you use a certain formula and figure out your yardage, and how many pounds of explosives per cubic yard does it take. Go from there.

The small explosives look like in the movies, like a candle with a wick in it, but what we used was anywhere from four to six inches in diameter, twenty or twenty-four inches long. The explosives were in cardboard tubes and you shoved one or more of them down the hole. Shooting out there at the gravel pits, why we’d just fill the holes full of that.